BioShock's Failed Fictional City Of Rapture Is More Rooted In Reality Than You Might Think

As BioShock celebrates its 15-year anniversary, we take a critical look back at the underwater city of Rapture and how it reflects real-world political impulses.

BioShock recently celebrated its 15-year anniversary. Below, we take a closer look at how the iconic setting of Rapture reflects real-world libertarian philosophies.

BioShock's Rapture always felt like someone else's dream, right from the start, and that's because it always has been. There may not always be a lighthouse, but there's almost always been a man wishing for his own city to serve his interests and needs.

Libertarians have been misunderstanding problems with society and trying to apply their top-down thinking to new settlements in remote places, far away from government rules and regulations, for practically as long as people have been telling stories of running off and starting somewhere new. It's easy to understand the temptation to just leave and make a new city, but the compromises that come with individual freedoms being limited are often part of what makes a society a place where people want to be.

After all, if people are completely free, left to nothing but their own decisions and desires, they're beholden or responsible to no one, so are you really part of anything at that point? Can you really make something detached from everything without leaving everything? Or would that simply leave you with less than what you started with? A man with ideas and visions that's more likely to harm groups of people not represented in the room.

15 years ago, BioShock flooded the world with the magic, wonder, and terror of what an isolated city built with absolute freedom in mind for individuals could look like. Everything from the art they create to the science they explore was subject to this freedom, for better or worse. And in the process, Andrew Ryan's Rapture also came further than any real attempt to start a successful city under or on the water.

Irrational Games wasn't shy about exploring the horrors of men left to nothing but their own ideas and devices, but the studio also had to embellish some parts to make a good video game.

BioShock ran further and instead pressed for what might happen if a remote settlement, influenced and driven by objectivism and the ideals of individuals like Ayn Rand, were to get off the ground and find full isolation away from the rest of the world. BioShock explored how citizens may act when their political and/or philosophical ideas or dreams were repressed and how business tycoons would act when only encouraged and never really regulated.

It's a big-budget video game, and so it doesn't take too long for people being able to shoot bursts of lightning, swaths of fire, or swarms of bees out of their hands, but Irrational Games also pulled back the corners of the more realistic ramifications of holding a system of beliefs over what's actually happening and the people affected by it. The city of Rapture allowed the ideas and motivations of landlords and shareholders to prevail over the everyday person. (Can you even imagine?!)

And yet, the fictional, fascist fishtank has more in common with most attempts at sea settlements than I would have thought, and I'm not talking about working plumbing or good music.

Irrational Games showed us a glimpse of minarchism, a form of libertarianism that works for a while in Rapture, but the player's experience starts in the middle of the ocean. From there, they walk into an isolated lighthouse and discovering an underwater city in ruin, tattered and torn apart by civil war and a man that now essentially holds the title of both god and king, two of the very things that drove him to the sea, but were now taking him beyond the sea.

Rapture's most foundational text is absolutely Andrew Ryan's monologue, which is used to sell the idea of Rapture as a city to people that think and see the world like Ryan, the city's founder and, ultimately, ruler.

The player character hears a recording of Ryan's now-famous quote as they make their way below the lighthouse, via a small bathysphere pod, unaware that what waits for them below could be more treacherous than the ocean waves of the surface.

"I am Andrew Ryan, and I'm here to ask you a question. Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow? 'No!' says the man in Washington, 'It belongs to the poor.' 'No!' says the man in the Vatican, 'It belongs to God.' 'No!' says the man in Moscow, 'It belongs to everyone.' I rejected those answers; instead, I chose something different. I chose the impossible. I chose... Rapture, a city where the artist would not fear the censor, where the scientist would not be bound by petty morality, where the great would not be constrained by the small! And with the sweat of your brow, Rapture can become your city as well."

Andrew Ryan is the founder of Rapture and his ideas and influences, and even reasons for growing disillusioned with the world really weren't that different from some of the most notable, real-life, libertarian seasteaders.

Ryan fled to the United States as a boy after being forced to flee his home country of Russia to escape political violence. He amassed a fortune in several ventures, most notably in oil, but his devotion to America turned to disillusionment after President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, among other political directives, began taking direct aim at helping poor people.

Ryan believed socialism and collectivism to be a great evil overtaking the country. America's use of atomic bombs against Japan during World War II provied to be too much--but not for the reasons you might think. The senseless murder of Japanese citizens at America's hands inspired Ryan to start work on his underwater utopia, though it was mostly because he took issue with a country using science and technology as a weapon in a war and less about taking issue with war crimes.

The real-life Republic of Minerva's start isn't too far from Rapture's, nor is its chief founder all that dissimilar from Ryan. Michael Oliver was saved by allied forces while on a death march from Dachau, one of the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. He immigrated to the United States and accumulated wealth in various business ventures, including a land development company and selling gold and silver coins.

Like Ryan, Oliver was upset with the direction of the US. He also shared the belief with Ryan that America was doing too much to help poor people with social welfare programs and took issue with what he saw as a war against the free enterprise system.

By 1968, Oliver had self-published a book, titled A New Constitution for a New Country, with his own constitution and ideas on how his libertarian society would function, were it free from an overreaching government. Like Ryan, his beliefs echoed the objectivism and property rights of Ayn Rand and other prominent libertarians of his time.

His book earned him more attention and made it easier to form the Ocean Life Research Foundation, thanks to additional help and investments from several other wealthy people who shared his beliefs and vision. The purpose of the organization is easier said than done: to create a self-governing country, separate from the United States and every single other country. A free and autonomous nation.

The open ocean felt like the best place to him because it felt like an unclaimed frontier. He just needed to find a way to make it happen.

By 1971, he and other investors were in the process of having massive amounts of sand poured over the top of the shallow waters of the Minerva Reef. Their plan, too, was to fill a new utopia with like-minded people. In fact, groups they disagreed with, such as the collectivists so despised by Andrew Ryan, weren't even allowed to invest in the Republic of Minerva.

Less than a year later, the settlers had been pushed out by Tonga, a nearby Polynesian island, which actually had enough legal claim to the area to do so. With their plan to create 2,500 acres of land in the middle of the ocean, eight feet above sea level, down the drain, Oliver began minting and selling currency for his fake country. It could be purchased with real money, and was all to help raise funds. However, raising money wouldn’t fix one key problem in Minerva’s failure, which was that the area belonged to an existing country.

There were a few small attempts at trying to recapture the failed dream of the Republic of Minerva but all hope has been washed back into the ocean. At this point, the only tangible proof that there was ever something even called the Republic of Minerva are the last pieces of remaining currency, which can often be found for sale on eBay for much more than it was ever worth.

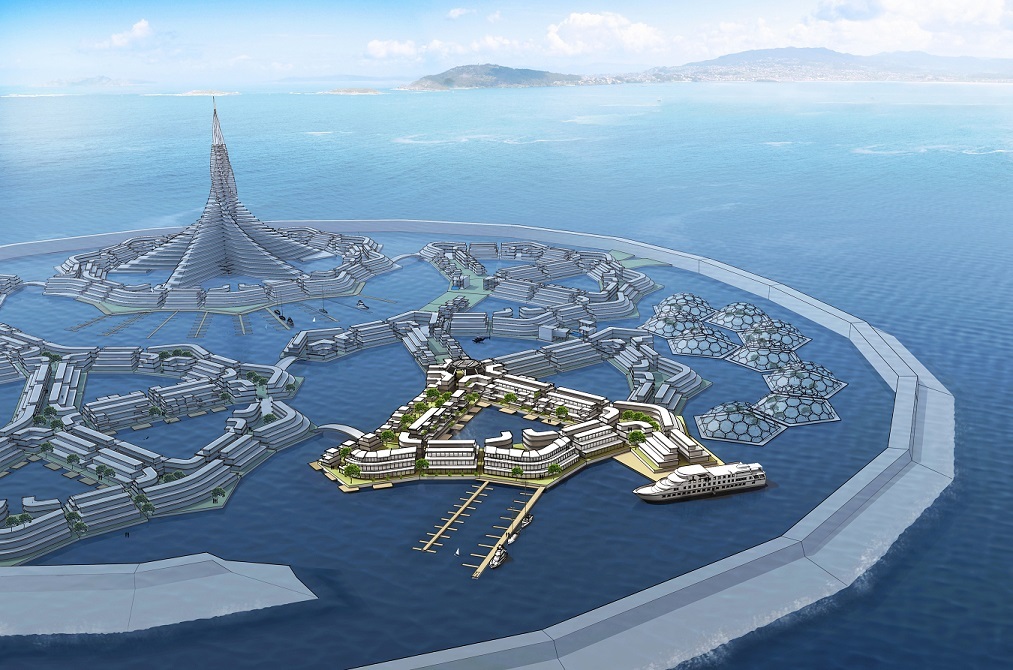

The Seasteading Institute has followed in the footsteps of the Republic of Minerva, though with a few differences. The organization was founded by Patri Friedman, a software engineer and political and economic theorist, and has been financially supported by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel. The organization's website states that it believes in creating floating cities, "which will allow the next generation of pioneers to peacefully test new ideas for how to live together."

The website also goes on to say, "Enrich the poor. Cure the Sick. Feed the Hungry. Clean the atmosphere. Restore the oceans. Live in balance with nature. Power the world sustainably. Stop fighting."

The organization's ultimate goal currently seems to be experimenting with floating cities that bubble out from above and next to other cities, which almost feels like life imitating art a little too much, given that a sequel to BioShock, 2013's BioShock Infinite, took place in a floating city, far up in the clouds.

Though the Seasteading Institute hasn't quite reached the above-the-clouds heights of BioShock Infinite and is instead aiming more for resorts and settlements that lie off the coast. Friedman has stated the goal is to both build new settlements that can exist alongside and above other cities and to disrupt and influence existing governments.

It's been difficult, and progress has been slow, since the goals of the Seasteading Institute don't really align with existing governments and countries. This is making it difficult since the organization greatly needs the support of another country to make it off of the ground, giving it somewhat of a parasitic dynamic with existing society and governments.

It's probably not a bad thing, though, considering how it went for everyone in BioShock Infinite's floating city of Columbia. In fact, we've seen how all that went. Multiple times. Again and again. And we've also now seen Bread Boy. I love Bread Boy.

As the climate crisis worsens and rich people continue to look for solutions that only they can think of and benefit from, it's become increasingly clear that the quest to colonize the ocean will only continue. Let us all hope we get something in between sand being poured on a coral reef and people screaming and shooting fire at each other through a never ending civil war.

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation