Gaming Has Already Grown Up

Tom Mc Shea examines the deeper themes present in games, and how the industry is more mature than some think.

Fun has become a dirty word. Both David Cage and Warren Spector--two prominent developers who have never been shy to express their opinions--spoke at length during separate D.I.C.E. sessions about the need for gaming to finally grow up. Emotional experiences that deal with relatable situations are paramount to raising this medium to a more substantial plateau, they argued, urging developers to push themselves to create mature and diverse games. But as gaming has grown and evolved through the years, a variety of interesting experiences have surfaced, making their cries for improvement ring hollow.

Their cries for improvement ring hollow.

Spector can no longer hold his tongue while the industry is flooded with mindless power fantasies. "If we're going to reach a broader audience, we have to stop thinking about the audience strictly in terms of teenage boys or even teenage girls. We need to think about things that are relevant to normal humans and not just the geeks we used to be." Cage echoed a similar sentiment. "We need to find ways to reach a wider audience. We need to move beyond our traditional market, which is usually kids and teens." Their underlying message is clear. The elements that have cemented gaming as an entertainment medium have ultimately hampered the growth of the entire industry. Without pushing beyond mere diversion, gaming will always be stuck in the cultural ghetto.

Cage and Spector (the creative minds behind Heavy Rain and Deus Ex, respectively) are two passionate creators whose cautionary words should be taken seriously. Those who have the most potential to steer how the general public views this industry are developers who create expensive games, and the biggest titles are more often than not flashy endeavors that emphasize over-the-top action rather than honest emotion. Striving for actual maturity is commendable, as opposed to the things the ESRB classifies as "mature," like violence, sex, and foul language. From the nascent days of this medium, games have been more concerned with fast reflexes and abstract puzzles than everyday problems, and that focus, Cage and Spector maintain, has cemented video games as a niche that encompasses little more than juvenile time wasters.

Without pushing beyond mere diversion, gaming will always be stuck in the cultural ghetto.

However, as earnest as Cage and Spector are in their claims, such accusations of eternal Peter Pan syndrome are disingenuous. Although the simple joy of hurdling a woebegone turtle as a potbellied plumber still delights the child in us all, and we're thrilled by a Spartan solider wakening from an eternal sleep to save humanity, there is nothing wrong with these endeavors. Games such as Mario and Halo offer an invaluable service that, in large part, defines the inherent appeal of video games, and Cage and Spector want to move away from these and other franchises because they cater to the kids and teens markets. Fun is the driving force of any entertainment field, and focusing on precise control and catlike reflexes is a culmination of what developers have been trying to achieve for more than 30 years.

Games concerned with nothing more than enjoyable entertainment should be celebrated, not shunned, especially because they are surrounded by others that show serious strides toward something more substantial. Cage and Spector are right that real problems should be examined within the spectrum of video games, but such a shift has already rippled through the silicon world. Metal Gear Solid 4 dissected warfare in modern times, postulating that conflicts were no longer being staged for ideological differences between opposing factions; rather, shadow corporations manufacturing state-of-the-art weaponry earned profits by convincing mercenaries to bear arms. Such an explosive topic was weaved artfully throughout an otherwise bizarre tale filled with clones and cyborgs, but that doesn't diminish the controversial message being outlined.

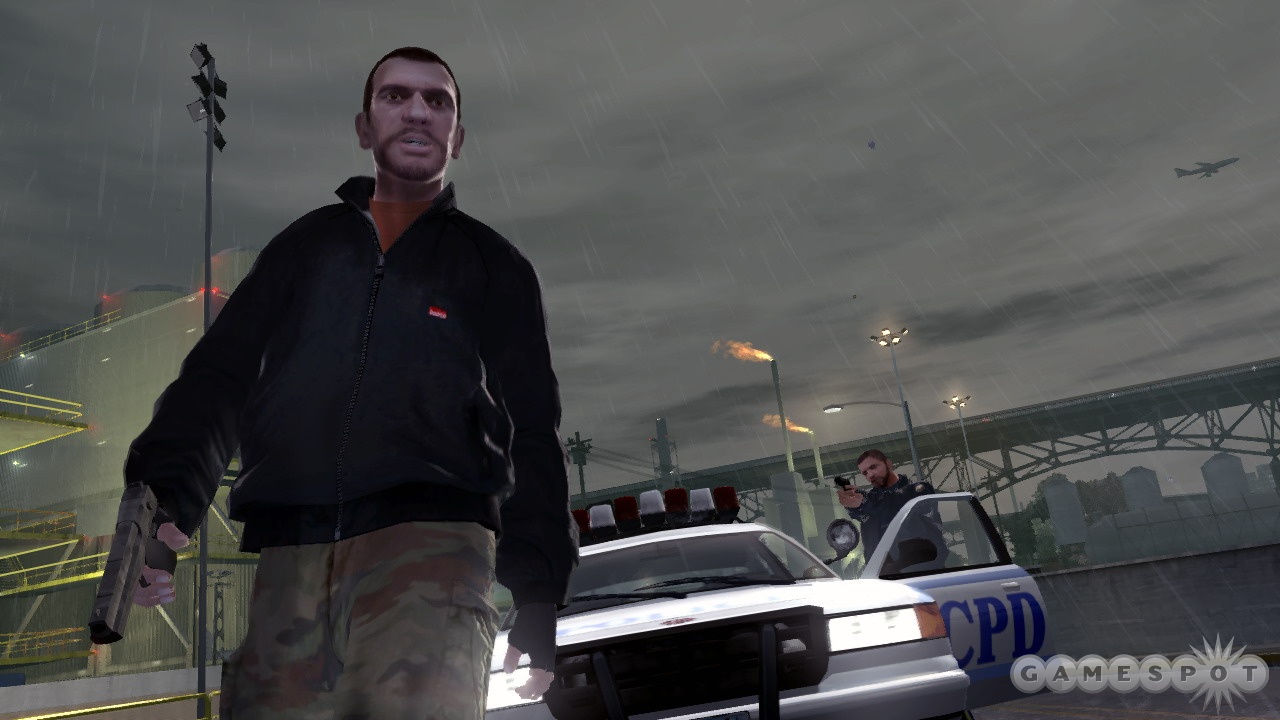

Grand Theft Auto IV used a similar method to explore its mature subject matter. Beneath the murder sprees and chase sequences lay an in-depth look at the troubled life of an immigrant. Fleeing to a country in which the system discourages social mobility, Niko struggles to break free of the shackles that chain him to a life of criminal servitude. Even Call of Duty, often maligned for its nonsensical explanations of worldly events, tapped into a disturbing reality in Modern Warfare 2. Tricked to take over an airport by force, you wade through crowds in a Russian concourse with an assault rifle cocked and ready. Do you walk by the screaming passersby, or fire blindly into the throng? And if you choose the latter, how does it feel to harm unarmed spectators? In a universe in which good and evil are defined by who stands beside you, how do you define yourself when the innocent fall by your feet?

How do you define yourself when the innocent fall by your feet?

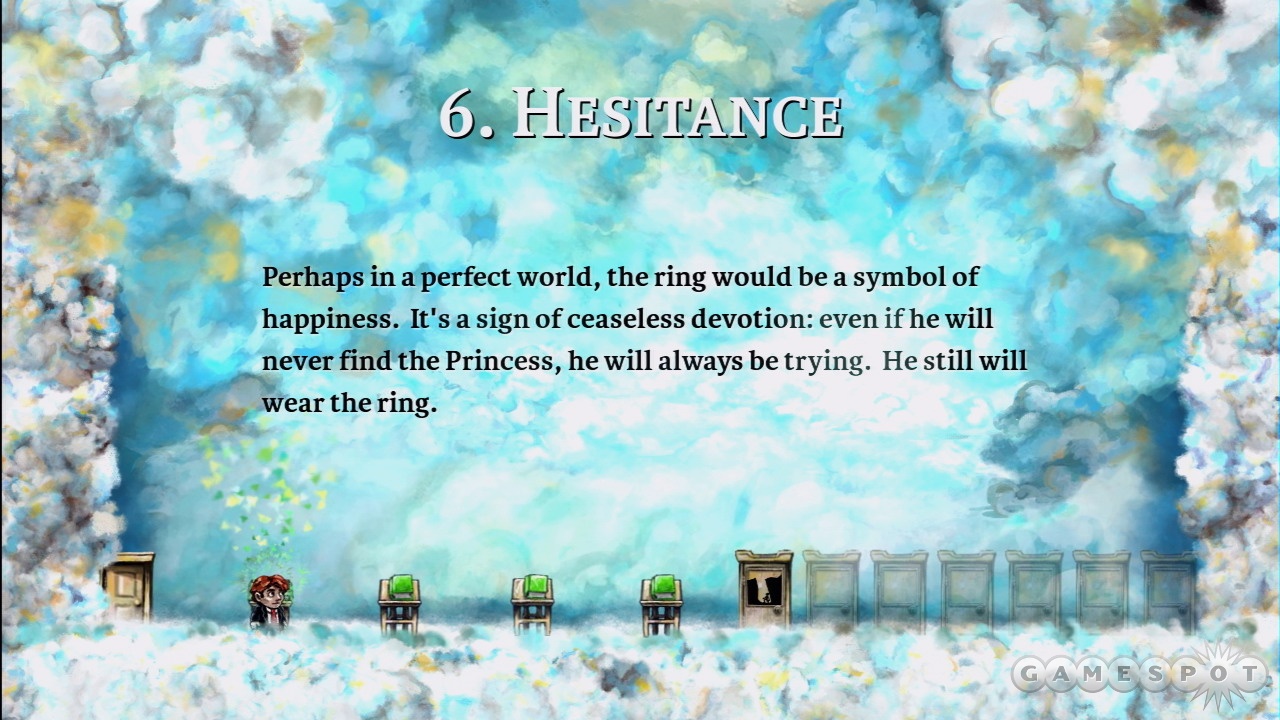

These examples show that not only has the progress Cage and Spector are striving for already been reached, but it has happened in some of the biggest, most commercially successful games available. If you look beyond the most expensive and well-marketed offerings, there is a nearly endless stream of games that examine issues paramount to our existence as human beings. Braid explores the obsessive yearnings of a scorned lover; Passage succinctly summarizes the travails of life; Persona 4 offers thoughts on gender identity, voyeurism, and overcommercialization. The industry is filled with smart individuals working on projects that push the medium forward. Interaction has allowed games to explore deeper themes in meaningful ways, and there has been a serious rise in mature content in recent years.

So, despite what Cage and Spector claim, games already explore real problems that the average person can relate to. However, that's not to discount what the two developers so passionately believe. Although there are plenty of games that willingly highlight important topics, admitting this truth is still taboo. Look, for instance, at how the themes of BioShock Infinite are communicated to the world at large. By glancing at the box art or the commercials that appear in movie theaters, it would be easy to assume this is another shooter in which you turn off your brain while you mow down your evil foes. But, if you read interviews with the development team, it's clear that the game has grander, more meaningful aspirations. Infinite, like its predecessors, examines the beliefs of our society if they're taken to the extreme. In the case of Irrational's newest game, that state of mind is xenophobia.

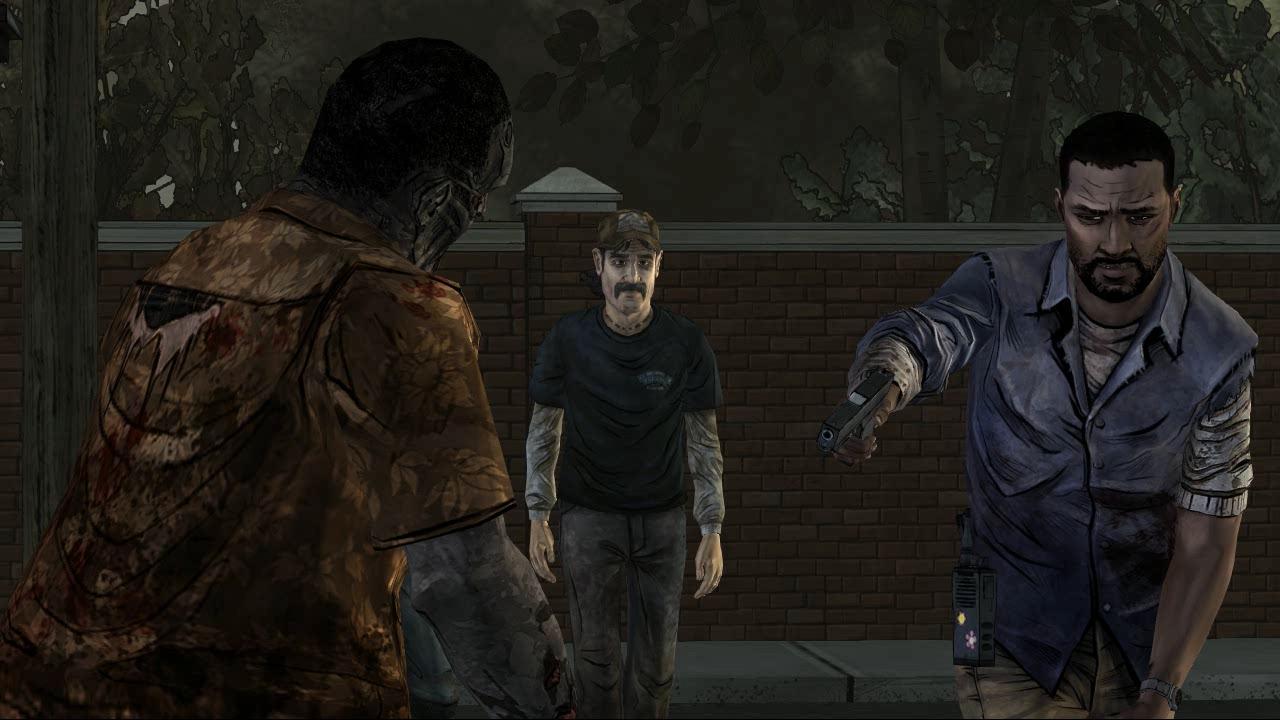

The fact that the marketing and development of BioShock Infinite have traveled along two very different paths does show that games still have a long way to go. Games have never been seen as inclusive entertainment to the world at large, and it will take many games such as Spec Ops: The Line and The Walking Dead to show that mature subject matter is possible in an interactive field. However, we are traveling along the right path. Big publishers may not readily advertise what their games contain, but they are funding projects developers are passionate about. And the independent community has seen bountiful offerings that explore the very themes Cage and Spector have proposed. It may take many more years before games are recognized as a valid form of artistic expression by the majority, but such a goal is already in sight as developers grow along with their audience.

'Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation