Once Upon A Time: Narrative in Video Games

In this GameSpot AU feature we look at narrative development in video games and the growing question among video game developers and gamers: are video games an effective storytelling medium?

When we talk about video games we often talk about the same things: gameplay, length, graphics, difficulty, multiplayer and online capabilities, how well it will sell, and who will buy it. But how often do we talk about the game’s story? How often do we discuss the effectiveness and purpose of its narrative?

In this GameSpot AU feature we look at game narratives, and ask the question: are video games an effective storytelling medium? To find out we talk to game theorists, scriptwriters, and developers from studios including Remedy, Quantic Dream and 2K Games, as well as the leading man of adventure games, Tim Schafer.

How do you tell a good story? If you’re human, it comes naturally. The innate ability to recount our experiences and use imagination to experiment without taking risks is an evolutionary trait that humanity shares across all cultures as a way to educate, entertain, and preserve ourselves for future generations. We tell stories through words, music, art, and dance; we record them on paper, paint them on canvas, and capture them on film. And now, thanks to video games, we can interact with them. When we play a game we are not merely passive observers; we become active participants in the story as it unfolds.

But while there’s no doubt video games tell stories, the nature of their interactivity raises the question of their potential to do this effectively. Comparisons to other storytelling media like film and literature are inevitable but essentially useless--each medium has its own advantage over others, and can do what no other can in accordance with its abilities. But some critics suggest that because games are interactive, their main focus should be gameplay, not story. Others believe that video games can, and do, successfully marry gameplay and story to become an effective storytelling medium. So who is right?

The interactivity hurdle

Earlier this year producer of Square Enix's Star Ocean: The Last Hope Yoshinori Yamagishi told Computer and Video Games Magazine that video games could only advance as a storytelling medium by overcoming the challenges of interactivity.

“It is more of a challenge to produce a game in order to tell a story. In TV, film and theatre, the creator has control over how he gives the story to the viewer--it's easier to control the emotions and feelings expected from the viewer,” Yamagishi told CVG.

“In [a game developer's] case we always have to think about how players might react to each depiction of a character or storyline, and that's the part we can't predict. But if we manage to get over this hurdle, then I regard video games as a greater medium to provide people with deep emotional and exciting experiences.”

Yamagishi is not alone in his view. Many video game theorists now believe that the interactivity of games stop them from being an effective storytelling medium. Much of the theory surrounding this topic explores how well video games master the relationship between story and the interactive element in games--gameplay. Denis Dutton, professor of philosophy at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand and co-founder of the renowned website Arts & Letters Daily, spent some time with Grand Theft Auto and BioShock to get a sense of how stories in games develop and work alongside gameplay.

“There’s a deep division between the concept of a story as it has come down through tradition and the concept of a story as it is in video games,” Dutton said. “Games do not have the story structure we see in Greek plays, Shakespearean tragedies, or even soap operas on afternoon TV. They are, at their very heart, games and not stories.”

According to Dutton, all stories have predetermined outcomes, whether it be Homer’s Odyssey, Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four or a joke told over a beer. When it comes to video games, however, the story element is little more than “window dressing”; the narrative is built around the characters and gameplay.

“The interactivity of games is both an advantage and a disadvantage. Of course it is fun to get your hands into a storyline and move it around as you would like. But what would happen if you could enter into your favourite film and do the same? That’s not how traditional narratives work.”

Video games may not work as traditional narratives, but they incorporate all the basic elements of storytelling, including the eternal human interests that are played over and over again in all stories across all media and cultures: love, family life, threats and dangers, exploration and adventure, mortality and death. Like other stories, video game narratives are a powerful expression of the human imagination--witty, entertaining, and complex stories.

“The difference is, of course, that video games combine these traditional elements with interactivity,” Dutton said. “I continue to resist the idea that this can be done easily or effectively. Video games are a new form of make-believe, that’s for certain, but I don’t think I’m ready to call them a new form of storytelling, and beyond that, an effective medium to tell stories. It’s clear to me that Grand Theft Auto and BioShock have more in common with a tea party for teddy bears than they do with the plays of Shakespeare.”

According to Dutton, the only way for video games to overcome the challenges of interactivity and become an effective storytelling medium is to successfully marry both story and gameplay in their development.

“Other storytelling mediums draw us into the inner lives of other people. Video games must learn to do the same. We as players must become completely absorbed in the fate and lives of the fictional characters on screen. It remains to be seen whether game developers can achieve this.”

The question of whether video games can be an effective storytelling medium has also interested academics, who have been debating the topic for years. Two schools of thought currently exist on the matter: ludology and narratology. The former argues that the focus of video games is, and should be, gameplay; the latter argues that video games can, and should be, a storytelling medium, and should be studied in the same way as other storytelling mediums.

Jesper Juul is a video game researcher at the Singapore-MIT Game Lab in Massachusetts, USA. He has been studying video games for the past 10 years, dedicating a large chunk of his early work to video games and narratives. Although his theories fit into the ludology school of thought, Juul also argues that video games can be both narratives and a set of rules at the same time.

“The game versus story problem really comes down to the obvious: stories don’t let users do things (only interpret) while games let users do things. Stories are fixed, designed experiences; games let players change things,” Juul said.

“I used to think that gameplay was necessarily more important than story, but I have come to accept that some gamers see things differently. When we play games we often switch between seeing the game as a set of rules, like collecting 10 stars to complete the level, and seeing the game as fiction, like recognising that Mario’s girlfriend has been kidnapped.” Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

The Donkey Kong example is a case where the rules of a video game cannot be explained by the story. Interestingly, Donkey Kong was one of the first examples of complete narrative in video games, cut scenes and all. The crux of Juul’s argument is that video games are an effective storytelling medium but only in the broadest sense; where it falls apart is the portrayal of human emotions, which Juul believes video games do very poorly.

“Sure, The Sims has characters with emotions, but they are pretty shallow compared to Dostoyevsky,” Juul said. “Complicated emotions and social relations in games often get delegated to cut-scenes, where developers are spared having to implement them in the game rules.”

Like Dutton, Juul believes the power of traditional stories lies in their fixed nature, where things must happen the way they do. This is at obvious odds with the interactive nature of video games.

“What works best in video games are the environmental narratives like in the Grand Theft Auto games. The environment and the radio stations and so on present a depraved and corrupt version of a modern city. This is combined with giving gamers freedom to perform a series of predefined missions at their own pace, which yield a narrative. In this case, gamers still have freedom in between missions.

“There certainly have been many games that tried too hard to tell a good story at the expense of the player; forcing the player to sit through endless cut-scenes and so on. It is easy to point to the failures, but some games are also successful--Final Fantasy, Grand Theft Auto and BioShock spring to mind.”

Other theorists have different opinions. Dr Souvik Mukherjee, a game theorist from Nottingham Trent University in England, strongly argues against the positions put forward by both ludologists and narratologists, choosing instead to focus on raising awareness of video games as an important storytelling medium.

“Video games are a new way to tell stories,” Mukherjee said. “Certainly, we don’t see the same Aristotelian plots with the same clear-cut beginning, middle and end, but an increasingly complex use of plot and generic conventions from novels and film.”

But while some games can effectively tell a story, others clearly cannot. Which points to another problem: some types of games simply don’t require an effective, or even a good, story. Should these games be taken into account when discussing the effectiveness of video games as a storytelling medium?

“If you are making a racing game like Need for Speed, or a super-gory shooter like Postal, then the story element won’t be a terribly important factor,” Mukherjee argues. “However, if you consider the Half-Life games, Max Payne, Metal Gear Solid, Fable or Fallout, the story and gameplay go hand in hand. These are the games we should be looking to for examples. I’m sure there are gamers who disagree with this point of view, but that’s the point about texts--they make you think and engage with them at various levels. It all depends on the developers and what they want to achieve.”

But developing a video game is no easy feat, and sometimes original intentions and ideas can disappear overnight when budget, time constraints and publisher demands are factored in. Only those who work in the games development industry know just how quickly things can change. Rhianna Pratchett, daughter of English novelist Terry Pratchett, is a video game scriptwriter from London who has had firsthand experience with the demands of the job.

She has been in the industry for 11 years, writing for titles such as Mirror's Edge, Heavenly Sword, Viking: Battle for Asgard and the entire Overlord franchise. While she sees video game scriptwriting as a fairly new discipline compared to other forms of entertainment writing, she believes the industry has a long way to go before developers get the right balance between gameplay and story.

“Video games are the medium with the most untapped potential when it comes to storytelling,” Pratchett said. “But there’s a long way to go. Developing the right synergy between gameplay and narrative takes time to become industry-wide. For every Portal or Psychonauts we have several dozen titles where the narrative has clearly been an afterthought and has no real bearing on the gameplay.

“Gameplay and story can sometimes have quite different goals that can often see them fighting for space. And nine times out of 10, story loses. It’s really about finding the common ground between the two and thinking about story early enough in the development cycle that it can properly fit together with the gameplay. Not just lie on top of it like a kind of narrative custard.”

Pratchett believes in the power of a well-told narrative working alongside gameplay, pointing to the fact that story and characters bring context and meaning to the gameplay experience, and can often be powerful motivational factors for players.

“Amazing gameplay can survive s*** storytelling, it’s true, but I believe it’s poorer for it. Great gameplay, infused with a strong narrative and story world, is the ideal.”

But this is easier said than done. Mirror's Edge, last year’s first-person action game from EA DICE, received criticism for its mismatch of gameplay and narrative elements. GameSpot reviewed the game and gave it a score of 7, calling out its “tedious jumping puzzles” and “hazy objectives”. Pratchett says she was brought on to the project quite late, which impacted on the available narrative structure more than the developers imagined.

“I think things will be done differently in the future, put it that way,” Pratchett said. “DICE had problems finding a writer; by the time I got there all the levels had been designed. To be able to make a scene truly interactive (especially one with a first person viewpoint) you really have to design the world to support it. If you don’t then you end up only having linear and often expensive options at your disposal, which don’t always fit with the gameplay. We didn’t get to do as much environmental storytelling as I would have liked.”

Pratchett's experience points to the overall importance of professional story writers in video game development, and their integration within the team of developers.

“When I first started out I used to think that bad game stories or dialogue were the fault of whoever was listed as the writer or story creator. That somehow they didn’t get it. I now know that this is, for the most part, ridiculous. It’s much more likely to be down to the story being a last minute thing, poor integration, or the writer being poorly managed or not having access to the development team. Plus a hundred other reasons that games writers have to tackle on a daily basis. When it comes to writing for games it’s not merely down to how good you are, but how good you’re allowed to be.

“I guess the prominence of some of my games has allowed me to get people discussing games narrative a bit more, and hopefully encouraged developers to think about how to make better use of professional storytellers.”

This was certainly the case with Practhett’s work on the Overlord franchise, which began when a fellow writer recommended her to Codemasters. At the time, the publisher and Netherlands-based developer Triumph Studios were looking for a very specific narrative tone, which Practhett managed to provide. Since then she has worked on four Overlord titles, plus the expansion Overlord: Raising Hell.

"Although I wasn’t onsite that much I had a close working relationship with the team, who are a hugely talented bunch," Pratchett said. "Things like MSN, SVN, wikis and ICQ helped immeasurably, and allowed for regular contact and keeping everyone on the same page. I also worked closely with the individual designers to make sure that that every level served both the needs of the moment to moment gameplay and the story. I think they really helped create a greater cohesion between the two elements.

"Writing is rewriting, as the famous phrase goes, and nowhere has that been more the case than in games. It’s a highly iterative process. Smart integration is fundamental, as is giving narrative professionals a little bit of room to play."

If the successful marriage between story and gameplay ultimately lies in the hands of game developers, then what do the developers of story-driven games have to say about the medium and its storytelling capabilities? Do they know whether games will one day stand shoulder-to-shoulder with novels, films and plays? Or will their interactivity restrict them from ever being regarded as an effective storytelling medium? Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

In Part One of Once Upon A Time: Narrative in Video Games we looked at video games as an effective storytelling medium as discussed by game theorists, academics and a video game scriptwriter. In Part Two, we speak to the people who set the rules by which we play, and ask them to weigh in on the debate.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle once said that a story need only have a beginning, middle and an end. If Aristotle is right--and who are we to argue with one of the greatest thinkers of all time--then we should learn to see video games as just another branch of an already diverse storytelling tree. It’s true that games present stories in a different way to what we’re used to, but at their core they are just as effective at telling these stories as any other medium. We already know that some games do not aim for, nor require, a good story to support their gameplay. And as we have already seen, the interactivity of games encourages--rather than inhibits--good storytelling, heralding in the natural evolution into non-traditional forms of narrative.

So what does this medium mean to those who create games? Do developers agree that video games are an effective storytelling medium? Are we now starting to see more games that aim for that perfect balance between gameplay and story?

What the developers say

Sam Lake is the first to point out that creating a good balance between story and gameplay during the development process is anything but easy. As the lead writer at Remedy Games in Finland, Lake is responsible for the creation of one of video game history’s most memorable characters. Max Payne (the character) was a hit with gamers for his quirky metaphorical reflections on life and his somewhat gritty social interactions. Max Payne (the video game) doesn't follow a traditional linear narrative structure, beginning in the middle and using flashbacks and dialogue to reveal past events. The game’s film noir style mixed with its unique way of graphic novel cut scenes earned it stellar critic reviews and helped it win a coveted BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television) award for best PC game of 2001.

Lake, who studied both literature and screenwriting at university, has worked on all of Remedy’s titles, including Death Rally, Max Payne, Max Payne 2 and the upcoming Alan Wake. He says that creating a game with good story and good gameplay is extremely hard for a developer to do.

“You need to develop the two hand in hand,” Lake said. “You need to understand both, and you need to have lots of patience and be willing to put a lot of time and effort into making sure that both work individually and together. Very often, one or the other leads, and in concentrating on only one, you limit the other and end up in a situation where you need to make compromises. It’s a challenge, but it’s not impossible. I feel that it’s a goal worth striving for.”

Lake’s favourite part about his job is simply the act of being able to tell a story: from the original vision to the minute details like the individual lines of dialogue or the names and slogans on posters found in-game.

“In Max Payne and even more so in Alan Wake, the story, the character, the setting and the style of the story have all been part of the design process from the beginning. They are story-driven experiences. With both games I very much enjoyed borrowing classic and familiar elements from popular culture, things used in other mediums, bringing them to a game and using them in a new way in that context, creating a new, unique mix out of those elements."

“Every game is a combination of different elements," Lake continues. "Whatever works for that particular game, whatever makes it entertaining, engaging and interesting, is okay. Very few people care about how you do it, as long as they enjoy the end result.”

Jack Scalici, director of production at 2K, doesn’t agree with Lake. He believes there’s nothing simpler than making a game with perfect balance between story and gameplay. Scalici served as a writer on 2K’s upcoming title Mafia II, which is being marketed as a heavily story-driven game.

“When we looked at what made the first Mafia game so special, we all agreed that it was the epic story and the atmosphere,” Scalici said. “Unfortunately, the storytelling in many games will often take a backseat to gameplay. Storytelling costs money, and many developers will decide that it’s just not worth it, or that what they have is good enough. Publishers and developers can get away with this if the gameplay is great; gamers will often forgive poor storytelling, as will many reviewers.

“Personally, I don’t think it’s very hard to create a good balance between story and gameplay. I can think of many games that have gotten it right. It’s all about the game the developer chooses to make, and their aptitude. I think the problem exists because historically, the story of a game has usually been an afterthought. I would love to see this change.”

Scalici says that while some of his favourite stories have come from video games, he still believes gameplay is king.

“No matter how good the story is, if you don’t put effort into your gameplay, your game will fail. Gameplay, compared to story, is not as easy to get right. You need to start building the game and experience it before you can decide if it works or not, and getting that first playable demo done often takes a lot of people, time and money. This is one of the main reasons that development has historically started on games well before the story is close to final, and it can easily lead to an imbalance of the two.”

But once the gameplay is sorted, how many developers actually pay proper attention to getting the story right? One of the biggest reasons why so many games fail in the story department is that the developer has not invested time and resources into finding the right person to actually write a good story (i.e., not the work experience kid). Scalici agrees. He says the best-written games usually have one or more people who do nothing but work on the story element. Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

“A writer understands story structure and character development,” Scalici said. “They know how to exploit the strengths of the medium while keeping the scope of the game within the limitations of the current technology. Developers are famous for having an inexperienced employee, who usually pulls double duty as the junior production assistant or the IT guy, create or supervise the game’s story; this is a recipe for disaster. On the other hand, hiring someone who knows nothing about game design will lead to a story that feels tacked onto the gameplay.”

So while no one is prepared to disagree with the idea that storytelling is an important aspect of game development, just how many developers are actually devoting a good amount of time and resources refining the story element in their games alongside gameplay?

One developer who is doing just that is 38 Studios, based in Massachusetts, US. The studio was founded by Major League Baseball pitcher Curt Schilling in 2006, and is currently in the process of making its first game--an MMORPG codenamed Copernicus, which is scheduled for release in 2011. Knowing the importance of story, especially in an MMORPG, the studio brought on-board New York Times best-selling fantasy author R.A. Salvatore, who is now the lead writer and ‘world-builder’ on Copernicus. Salvatore is a gamer himself and no stranger to writing for the medium: one of his first projects was working on Atari’s Forgotten Realms: Demon Stone; he also served as editor on the EverQuest book line. It was that particular story that led Salvatore to realise to the storytelling potential of video games.

“From the moment I walked onto the world of Norrath, I knew I could write a thousand books set there--it was that alive and real to me,” Salvatore said. “What I came away with most is the nagging question of what the author’s role might be in a video game world.

“I like to make things fit together, logically and reasonably," Salvatore said. "I want a consistent world, with economics and politics that make sense, and magic that makes everything else fit its own reality. I don’t think we’ve tapped the full potential of video games just yet; we’re still working our way through the infancy stage of the medium.”

Salvatore returns to the idea that ‘traditional’ forms of narrative do not work in video games; no one wants to read three pages of text in-between levels or follow a story in exact chronological order. In this case, the interactivity of games is a redeeming factor.

“When you read one of my books, I’m in almost complete control. I create the heroes and invite you to live vicariously through their adventures. But video games take this to an entirely new level. In a massive multiplayer online role-playing game, the characters I and my team create, no matter how wonderful we might think them, are, by definition, secondary players. The most important character in a MMORPG is the one the player creates.

“But this doesn’t mean that there can’t be storytelling. What it means is that it’s up to us, the world-builders; to create a consistent, believable, beautiful and magical environment for the player, give him or her tools to write his or her own heroic adventure. If we can bring it to that point, well, that’s storytelling.”

Admittedly, it’s not always easy--or cheap--to take these kinds of chances when you’re a developer, especially when so much of the development process is trial and error. But Salvatore thinks it’s always worth trying for the sake of progress and pushing the medium forward.

“It’s kind of frightening when you look at the money involved in taking these chances, but it’s also exciting to be on the front end of it all. We’re going to try many different techniques to get our story across and make it important to the players without interrupting their gameplay. We’re going to watch and see what works and what doesn’t and constantly refine our delivery. And no one said it was going to be easy.”

Someone who has succeeded for years to create captivating, exciting and immersive video game stories and characters is founder of Double Fine Productions, Tim Schafer (recognised by many as the king of adventure games). Schafer is best known in the game industry for two things: making games that are funny and making games that tell a good yarn.

“I think people often see examples of story done poorly in games, and based on that they assume that story doesn’t work in games,” Schafer said. “Gameplay, story, art, and music--all of these are just tools to me, and they all serve the same purpose: to entertain the player and transport him or her into another world, and another state of consciousness.”

According to Schafer, good storytelling in games is all about empathising and relating to the on-screen characters, something that he believes games do very well.

“When it’s done right, you take on the plight of the protagonist as your own. You feel what they feel, and you are rooting for them because their success is your success. That’s even truer for games because their success is literally your success. That feeling of exploration and projection into a different world--no other medium can do that as well as games.

“I love it when fans write letters saying they had a really personal connection to a character. We got a lot of fan mail about Glottis [from Grim Fandango], for example. People really seemed to empathise with him, and share his emotional ups and downs. That’s so rewarding because it means that the character really came to life for someone.”

Like Lake, Schafer believes getting the balance between story and gameplay is a difficult thing for developers to do, and something that should be more widely celebrated when it is achieved.

“Games are full of trade-offs. There will come a point while making a game where you will have to sacrifice, for example, visual quality for a more dynamic environment or story for the sake of gameplay. You try to have everything, of course, but at some point you need to make choices and then you really need to know what your priorities are. I try to explore areas in games that I think haven’t been explored yet. Kind of like the Starship Enterprise. When any developer does that, it’s a healthy thing for the industry.”

So does that mean that video games will one day have the same reach as more traditional forms of narrative, like books and film?

“Yes, definitely. As soon as everybody over the age of 40 dies. Hey, wait. That’s me!” Click on the Next Page link to see the rest of the feature!

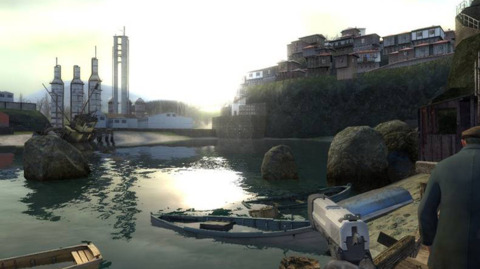

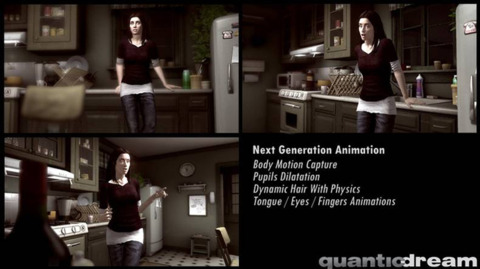

Reaching this goal could happen sooner rather than later, if some of the soon-to-be-released games--and the technology behind them--are anything to go by. One of the highlights of this year’s Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) in Los Angeles was the upcoming Sony-exclusive title Heavy Rain: The Origami Killer from French developer Quantic Dream. Quantic Dream’s founder David Cage says the studio has invested in proprietary technologies for many years, including a PlayStation 3 3D engine, to create what he calls "real-time emotion" within games.

“Creating emotions through interactivity is what motivates me,” Cage said. “When you look at a painting or watch a movie, the pleasure of the action does not come from standing in a museum or sitting in a cinema, it comes from the emotions triggered within you. In other arts and entertainment forms, these emotions are very diverse and intense. Reading a novel, you can smile, cry, be upset, feel empathy, etc. When you play a video game, all you can feel is anger, excitement, frustration, and competition--very primal emotions usually related to adolescence. All the more complex and deeper emotions found in life and other art forms are almost not present at all.”

Cage says that although these emotions are satisfying for younger audiences, they are not appropriate for an older audience. He believes adults want a more engrossing experience with more varied, intense and complex emotions. Most of all, they want an experience with more depth and meaning than what he believes most games currently have to offer.

“Like with the best movies they have seen or the best books they have read, they want the experience to bring them something; not only entertain them but change the way they see things. This is the challenge of our industry--choosing between being a toy for kids and becoming an art form for a wider audience.”

But there are many who would disagree with Cage. Surely we have seen more than enough examples of games with complex emotions--it’s hard to believe that all you’re ever going to feel while playing games like Shadow of the Colossus, Metal Gear Solid and Final Fantasy is anger, excitement, frustration, and competition. But Cage wants more--he believes the video game development industry needs to move into a new territory.

“All games look the same because we have exploited to the bone the potential of our current game paradigms. How many different games can you make where you shoot enemies in first person? You can make them look better, improve AI, graphics, physics, and so on, but fundamentally, the experience is still exactly the same. If we don’t invent new paradigms, if we cannot address the evolution of the market demographics and offer new kinds of experiences for an older audience, we will become no more than toys.”

Cage believes storytelling is one possible answer. However, this is not without its problems, namely publisher demands and a different set of development skills.

“Producing and selling games to a mature audience is a different job that requires a different strategy. I am sure that the market itself will help them [publishers] to understand the need for change. They [publishers] did not have a clue about emotion five years ago; today you cannot find a publisher who is not telling you that his product is emotionally involving.

“The second issue is that there is no grammar for interactive storytelling at the moment and very few people in the world working on this. I think Heavy Rain is the only AAA title based on interactive storytelling in development at the moment. Working on this new generation of experiences requires a very different type of skills.”

For example, instead of having levels designers define where enemies and ammo should be placed on the map, Cage would like to see writers creating appealing stories and characters. With this new format, he hopes games will one day be created by authors.

“I don’t believe that games should be ‘fun’; I prefer to say that like any other form of entertainment, they should be engrossing and make you feel different things. I hope that Heavy Rain will demonstrate that in a way that will inspire other people to try this new direction. This is maybe the biggest step the industry has to make.”

Cage was inspired to create Heavy Rain after the agonising experience of temporarily losing his six-year-old son while shopping with his wife. The panic, despair and guilt suffered during that brief period led Cage to try a different approach in his work: writing something more personal, more related to him as a human being, as opposed to “heroes saving the world”.

“Writing about something that happened to you is a very different approach. Few games have done that before I think, because most games are about ‘out-of-this-world’ stories. I have never been a soldier during World War II, and I don’t know what it feels like to save the planet or to be confronted to hordes of zombies, so it is difficult for me to write about that. Talking about my son and what I felt during these 10 minutes is definitely something I found more interesting and more challenging. Our medium is now mature enough to tell stories about real people in real life. I don’t think we need aliens and monsters anymore.”

And that aspect of Heavy Rain is certainly evident to anyone who has seen it. The game tells its story through gameplay consisting of quick time events and a completely contextual interface, by which the characters have access to a large number of actions as required by the situation they find themselves in. In addition, playable characters can also die--when this happens gamers take control of a different character and the story continues along a different path, with certain consequences. If all playable characters die, the game ends with a proper conclusion. Cage’s goal in doing this was to leave an imprint in the mind of the player.

“We dared to break with the traditional game paradigms because we believe they are irrelevant for the experience we want to create. Ideas like game over, ramping, mechanics and so forth are of no use in this new format. We replace them by emotional involvement, decision making, and contextual actions.

“I think it is possible to create interactive experiences that will be a part of people’s culture, will contribute to make them who they are, will maybe even change them or make them think differently. We are just at the beginning of this.”

But while some developers already recognise the potential of video games as an effective storytelling medium, it may still be some time before the rest catch up. The ability to create fantastic, moving experiences in video games is already there--if this small group of developers can continue to invest in this vision, and the player base can continue to support them, then the medium can only grow stronger. What are your thoughts on video games as a storytelling medium? Can games tell stories effectively? Tell us your comments below!

Got a news tip or want to contact us directly? Email news@gamespot.com

Join the conversation