Fable III seems to be designed for the type of person who still has trouble finding that lever.

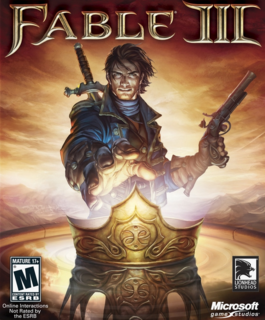

In what I can only assume is an effort to join what creative director Peter Molyneux terms the "triple-A club," the crew at Lionhead has worked diligently for years to make the Fable series accessible to even the lowest of the low common denominators. As Albion itself has progressed into the future -- from the first game's medieval fantasy to Fable III's industrial Victorian age -- so too has Fable's design marched inexorably towards a more modern vision of how best to ferry players through a game world. This vision is, unfortunately, growing increasingly blurry with each iteration.

Take magic, as an example. Long gone are the days when Albion's heroes could zip in and out of combat with charge and teleport spells, grow gargantuan, bend enemies to fight for their cause, or (most importantly) exploit combinations thereof. Fable III's limited repertoire of spells acts as another method of inflicting ranged damage, essentially rendering far-less-effective guns redundant. The new spell-weaving mechanic that grants you two magic-blasting gauntlets doesn't help heal the wound much: Casting two spells simultaneously isn't all that thrilling when said spells are dull. Lionhead giveth, but new concepts never seem to make up for what they taketh away.

Social interactions are similarly simplified, but for some unfathomable reason, forging friendships now requires more time spent mucking about than ever before. Unlike their easily awed predecessors, the peasants of this Albion don't really seem to care all that much about the hero -- or monarch -- in their midst. To win them over, you need to interact via a system of expressions, much like Fable II. Unlike Fable II, however, moving up each "tier" of interaction (neutral, friend, love) requires completion of an insipidly dull relationship quest -- fetch this, deliver that, drag target on a date. Even more annoyingly, the halt-the-bouncing-ball mechanic used to trigger more effective "sweet spot" expressions in Fable II was apparently too difficult for some, now replaced by lengthy button holds. If only maintaining real relationships were this easy: Interact, hold button, hold button, fetch garbage, hold button, marriage.

The ultimate goal of collecting buddies is the overthrow of Albion's king, your brother and a generic Very Bad Man who rules with an iron fist. Once this task is complete, near the end of the game, Fable III puts on its third hat: part action game, part social simulator, and finally, part mediocre kingdom sim. Kingship is essentially just a series of morally clear-cut but financially challenging binary choices (will you build the whorehouse or the orphanage, my liege?), presented on an exceedingly short timetable that leads to the game's climax. These decisions are meant to be difficult (the royal treasury's cash-on-hand is directly tied to the wider story's outcome), and keeping your revolutionary promises is immensely costly.

Too bad money is so ridiculously easy to accrue that Fable III's silly shift into a morality tale about the burden of the crown falls flat. Buy a house, rent it out, buy a shop. Repeat until your personal fortune can alter the course of Albion's history and still leave you with a Scrooge McDuck-sized pile to swim around in. Then, after the money is spent and the climactic finale occurs, the monarchy means little more than the occasional snap-to salute from Albion's soldiers and a snazzy set of clothes to wander around in.

If I seem overly critical, think of it as tough love from a concerned fan: Fable III is a good game, and the Fable series is still one of my all-time favorites. The Sanctuary system (pausing the game brings up a room full of menu options to navigate, rather than an interface to lag through) is a stroke of genius, something that every designer working in the action-role-playing genre should seek to emulate and improve upon. Albion is as charming and funny as ever, though some of the self-referential chicken humor is getting downright cringe-worthy. You'll find more side quests here than in any other Fable game, and solving some quest chains changes the physical makeup of Albion, opening new areas for exploration.

One particularly hilarious quest midway through the storyline speaks volumes about the difficulties of designing a modern game. A group of dorks in Bowerstone insert you into a game of their own creation -- basically Albion's version of Dungeons & Dragons. As you traipse through their world, the three dungeon masters argue with one another over various aspects of their design. Should opening this chest be optional or mandatory? Should the player be forced to speak with all of the townspeople, or should he be told which one holds the information he requires? One room in their game consists of nothing but a single, brightly lit lever in a pitch-black chamber with several large, vibrant yellow arrows dangling from the ceiling -- pointing directly at the lever's location. Fable III seems to be designed for the type of person who still has trouble finding that lever.