A Mostly Sunny Life

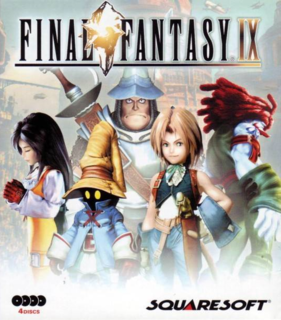

If we consider the life of Final Fantasy from its origins, when characters moved like pixilated beasts, to Final Fantasy VIII, when characters moved like full-bodied humans, then Final Fantasy IX resembles Zidane Tribal: half-man, half-beast. Zidane, a short yet nimble human with the tail of a monkey, is an odd choice for a main character but quite fittingly embodies the message that "old doesn't mean broken". Gameplay elements, new and old, combine together to compose an easy, breezy romp through the pages of Final Fantasy. Take one look at the cover - big heads, small bodies, and a black mage, all in happy-go-lucky colors - and you will remember the days before the growth stunt into the third dimension. Nostalgia speaks loudly in Final Fantasy IX, if not too loudly. At times, this four-disc adventure feels like a disjointed kindergarten song: "...chocobos here, moggles over there, here a card game, there a summon, everywhere a plot thread..." The game sings along our memories without knowing what it wants to say. Through all of its play, however, Final Fantasy IX has the innocence of a child - the power to undo old age. It does not run through the historical halls of Final Fantasy because it's stupid and immature. It does it because it's fun.

Child's Play

The world of Gaia is a bucket of watercolor that spreads its fine paint into imagination. It will open a landscape filled with flying ships, grand castles, and Renaissance flair. Smooth, round palettes brush the scene from the first moment you aboard the M.S. Prima Vista and step into the streets of Alexandria. Every floorboard, every flower, every lamplight and shade, shows life in its most vibrant color. So refined is the detail that you will play, entranced in the fairy tale, merrily and undisturbed; that is, until you stop, step back, and admire the shadows and lines in every crevice and corner. Even as you sprint across verdant fields, thrust your sword into gnarled monsters, and summon eidolons of awe and majesty, the still backdrops will move you. The warmth of the world sways like a field of un-plucked cotton, seamless and gently magical.

Whether you are skipping along the forest trail, splashing the puddles of Burmecia, sailing through the clouds with a mechanical ship, or swishing your legs upon a fluffy chocobo, you will hear melodies that will remind you of childhood. Nobuo Uematsu orchestrates cheer, in its bubbly tones, with such incredible range that melancholy songs gain poignancy simply by contrast. Princess Garnet's lullaby is an empathetic solo reflecting her lonesome yet kind heart, and the theme for Burmecia - The Land of Eternal Rain - cascades through minor progressions, medio-fortissimo, and arpeggios without rest. The spectrum of compositions, instruments, and rhythms will have you appreciate music in its many colors. Unfortunately, the musical paint is spread thin among ninety-one tracks. Though the light and charming themes are comforting, you will detect an air of immaturity. Don't expect to hear anything dramatically rich like One-Winged Angel from FFVII or Liberi Fatali, the opening theme for Final Fantasy VIII. Battle music, in particular, lacks dynamic urgency, neither rising nor falling enough to make you care about fighting. To a kid, though, such analytical nuance doesn't matter. The music will run to you, smile, and show you a finger-painting splatted with a mishmash of bright tone colors, and you just won't have the heart to say anything but that it's wonderful.

Teenage Traps

As you hop-scotch through your adventure, you soon learn an inevitable fact: life isn't all just fun and games. The world has rules, and as you try to fit those rules into your once fun-filled life, you will scoff at how unfair everything is. Balancing old mechanics with new ones is problematic, especially for a game that wants to both please its fans and reach a new audience. Though Final Fantasy IX is amusing and approachable - FFIII and FFVII easter eggs will surprise fans often, and mechanics are simple and traditional - characters have rigid roles, either as physical attackers or magic users. This over-simplicity constricts your decisions in combat and limits the flexibility that a materia system from FFVII or a transferable magic system from FFVIII would allow. Furthermore, it stereotypes the abilities of your characters to their personality. Vivi is a black mage that casts elemental spells and Steiner is a knight with sword abilities, and that's all they'll ever be. This caste system would be fine in the early days of Final Fantasy, but the lack of customability is too much of an unnecessary step backward.

New equipment-based skills try to make up for that customability, but they don't give you the same sense of freedom that the sound and graphics do. Granted, learning and setting skills is at least simple. Weapons, gear, and accessories all give specific skills to specific characters - some ribbons truly are magical - and by killing enemies, characters can learn those skills permanently. Using shiny aquamarine stones for reusable skill points, you can turn skills on and off, but more than a few flaws crack this simple system. For one, you can only learn what your skills actually do by switching out of the equipment screen and forcing your way to, from, and through the exhaustive skill list. Wasting your time even further, skills are the only way you can prevent negative statuses like poison and confusion, but there are status effects - and severe ones at that - which skills don't account for. Having no defense against Berserk, Mini, Death Sentence, Virus, Trouble, Zombie, and Instant Death is not just unfair, it's neglect. Until the end of the third disc, enemies don't inflict statuses often, but later bosses - particularly the last one - abuse your lack of immunity viciously. Sure, you can use items, but they are only temporary, case-by-case cures. In fact, since death removes nearly all status effects, you will resort to killing off your characters and reviving them later. Such a strategy has you realize that no matter how powerful your characters are, they will die.

Older and Older

As you slowly reach the end, the game will begin to lose its creativity - its inner child. Final Fantasy tradition bars FFIX's battle system, magic system, and practically every other system under a common guise: Why change? You certainly cannot fault the game for immersing you in a fantasy that works and still works here. The blend of ATB battles, "-ara" and "-aga" suffix upgrades for elemental spells, cinematic summons, feathered chocobos, waddling moggles, and an outrageous cast of characters on an outrageous adventure is a signature formula that has worked wonders for years.

The magic, nonetheless, is starting to experience a mid-life crisis. Limit Breaks are now erratically called Trance, except that it occurs automatically at random moments like an uncontrollable bladder. Standing in for save points are moggles - little animals that, of all things, now want you to deliver mail for them. If you ever wanted to know how a letter sorter feels, try remembering where Moguo, Mogryo, Mogki, and Mogmi are. If that bores you, why not try a card game, ala Triple Triad from FFVIII, called Tetra Master, a game that requires skill, fortitude, a need to ask random strangers to play with you, and a willingness to receive almost nothing but a Collector's Rank for your efforts. Or how about going on a distant journey on a chocobo, digging for chocographs in mysterious lands, and realizing that this is just an elaborate rip-off from FFVII that tries to justify itself with worldly treasures and color-changing birds? What these side quests have to do with the game other than filler is beyond explanation.

Reminiscence

Looking back, the story of Final Fantasy IX is one that lives from moment to moment but doesn't hold its attention on any particular point. From the beginning, we see a conflict between officers and outlaws as Steiner and his Knights of Pluto try to save Princess Garnet from Zidane and the shipmates of the M.S. Prima Vista. Characters, revolving around the romantic story between Garnet and Zidane, also have their own conflicts: Freya wants to regain her honor as a Dragon Knight, Eiko doesn't want to be alone, and Vivi struggles with his self-identity. Dialogue reveals these conflicts with strong content and smooth transitions, using occasional one-liners that have a depth you wouldn't expect from such a cheery game: "The only thing about the future is uncertainty." Unfortunately, the plot employs more than a few fixed battles that force you to lose, taking the game out of your control. Moreover, although most character arcs reach resolution, they are usually forgotten as quickly as they came. By the end of the game, you will ask whether anyone, except for Zidane, has relevance to the plot. What is truth? Why am I alone? What am I here? Instead of focusing on the love story or any of the character's motives, the story concludes with pseudo-intellectual existentialism. Philosophical endings that suffocate in the overused device of an evil entity bent on total destruction are a trend in Final Fantasy that needs to stop. Powerful stories are built from layered character progressions and plot threads, not on a road full of one-stops, leading nowhere.

Memoriam

Someday, you will begin to regret life and the adventures you had. On a journey that lasted you a lifetime - within a mere hundred hours or more - there were hardships, mishaps, and conflicts. Then you remember what you had kept secret, what you had kept safe. Final Fantasy IX is like a family treasure, a charm that is passed down from parent to child, one generation to the next. The crystal embedded in its logo symbolizes two worlds of different meanings merging together: romance with philosophy, innocence with nostalgia, the old with the new, and man with beast. It will remind you of a time when all these troubles meant no more than a passing memory. All the things that the game breaks by running through the halls can be forgiven and forgotten. Returning you to your childhood is the power of the charm, whether it is cracked, chipped, or a round piece of plastic in a jewel case.