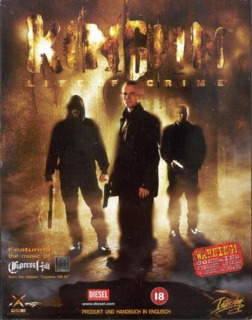

Radio City is dark, dangerous, polluted, verminous, decaying...and absolutely wonderful.

Kingpin is a dirty, dirty game, and I’m not just referring to the strong language about which the developers made such a cautious fuss in their numerous content warnings. Dirt and sludge covers every available surface, both indoors and out. Piles of trash and broken chunks of stone line the avenues. Every body of water – from puddles to rivers – looks like a polluted mixture of urine, gore, and gasoline. Again, even though it might seem that I’m describing Hell on earth, the amount of detail that Xatrix poured into Radio City by way of the timeworn Quake 2 engine was delightfully luscious. The game’s audio is also magnificent: every footstep crackles with grit and shattered glass, gunfire is loud and bold, bodies collapse with a meaty thud, the general clanks, rattles, and buzzes of a city environment are all around, in full stereo, at almost all times. Kingpin’s voice acting is okay: although those upstanding lads from Cypress Hill were an excellent choice for most of the game’s dialogue, the positive/negative exchanges in which the player can engage nearly everyone he meets were unnecessary and almost always moronically disjointed.

The enemy AI in Kingpin is remarkable even by today’s standards. While the computer-controlled friendlies in other games that were released at around the same time as Kingpin required plenty of babysitting – moving slowly to keep the trailing squadmates constantly in sight, taking care not to allow them to trap me in a dead end, or watching in horror as they wandered straight off of a cliff – Radio City’s hired thugs remained tight on my heels through every twist, turn, and crumbling stairwell. The only exception I noticed involved a patch of knee-deep water toward the end of the game; my pals completely forgot I existed as soon as my feet were submerged, but jumping in place periodically was enough to keep them on the trail. Unfortunately, that same brainy AI leads to some fairly serious problems in Kingpin’s combat mechanics. The perfection evident in a fellow thug’s ability to see his way through a gauntlet of obstacles also allows him to hit any target at any distance with little to no reaction time; if a direct line of sight exists between the player and a bad guy with a Tommy gun, then bullets are flying and health scores are dropping. Run and hide around a corner, and any enemies who follow will already have a perfect bead on the player when they spring into view. I never realized prior to Kingpin that programmers must bestow a smidgen of imperfection to their creations to include a more realistic reaction time from surprised goons, or a slight degradation in precision due to distance or recoil. Crossing certain boroughs without the benefit of some hired hands – who were blessed with the same eagle-eyed exactitude as Blanco’s boyz – became an overly-cautious slog that required more luck than skill (and plenty of flamethrower fuel, since no one shoots back when they’re flailing in agony).

Aside from its oddly infallible attackers and pointless conversation feature, Kingpin is an incredibly entertaining title. Even though most of Radio City’s hubs are cleared with little more than assassination assignments or key hunts (using severed heads and car batteries as a fitting replacement for more traditional tokens of passage), each new area feels like high adventure through an alien world. The industrial slums and seedy back alleys of Kingpin do exist in a portion of nearly every city in America, but not to such a pervasive extent. Wandering into the less-civil sections of town – willingly, with eyes wide open, and not while lost due to some bad directions to the stadium, to use a personal example – can be every bit as exciting as a trip to the surface of Na Pali or the bunkers of Area 51.