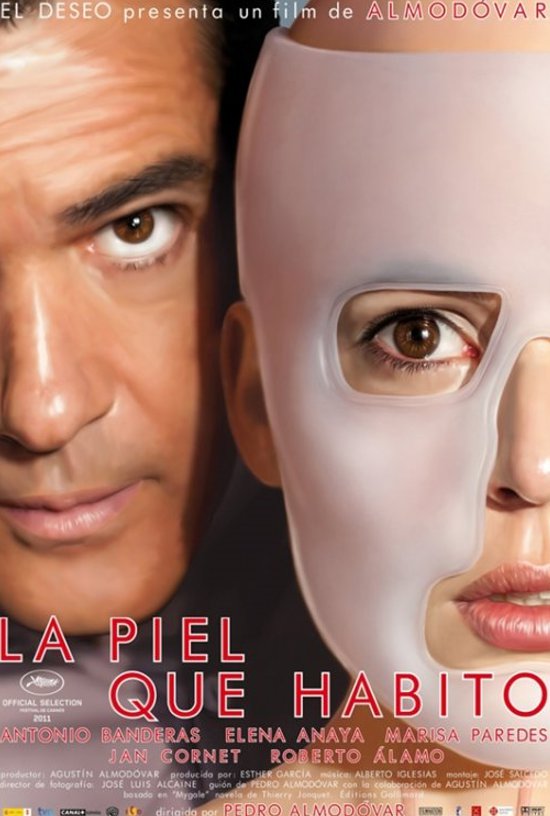

A woman named Vera (Elena Anaya) is being held prisoner in a beautiful manor home. She doesn't struggle and is offered proper food and materials through a slot in the wall. Holding her there is a scientist, Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), and his servant Marilia (Marisa Paredes). Robert is experimenting on skin grafting because he failed to save his wife after a car accident. He is not meant to be experimenting on people and is warned that he will be reported to a scientific board if continues his unorthodox approach. Trouble arises when Robert's brother Zeca (Roberto Alamo) arrives at the house, dressed for Carnaval, and tries to free the woman, thinking she is someone else. This leads to a flashback where we learn the rather tragic story of Robert's wife, his daughter and what led him to imprison the girl locked in the room.

Think twice about The Skin I Live In (La Piel Que Habito). That's not a question of whether Pedro Almodóvar's film is amiss or not. It is a masterfully told thriller but one that must considered strictly in terms of doubleness. This is a film concerned by doppelgangers, doubleness and repetition. In one of the opening scenes at a conference, Robert tells us that a face is part of the human identity. This is the basis for many of the film's cIassical philosophical questions, primarily how one can be in love with an illusion. It is Robert's intention to duplicate his wife through his experiments and research, negating genuine feeling and emotion. It most chilling conveyed through a voyeuristic framing device. Inside Robert's house is a large screen where he can watch the holding cell of Vera. He watches her on the screen, lying naked on her side, yet when he enters the room himself he sees that she has tried to kill herself. In this one sequence, we realise the power of human perception and by contrast, personal desire.

I'm also convinced that the film is also embedded in Platonic philosophy, specifically Book VII of The Republic: The Allegory of the Cave, where prisoners are chained up in a cave and can only view the shadows of objects. Plato associates real tangible form with knowledge. Consider that the characters in the film are like prisoners and that the bodies they've lived in are the shadows, what they believe are real forms in the world. Yet outside triggers, like in the case of one sad character a mirror, reveal the truth and the reality about their transformation and a new perspective on tangible form. Cinematically, Almodóvar has always been fascinated by Hitchcock-like dramas, involving murder, scandal and secrets. This film is, I think, his tribute to Vertigo (1958), which was also about a man fascinated by the duplication, perception and illusion of his wife, through an artificial embodiment. At its most personal though, the film is about Almodóvar himself, an openly gay man, acknowledging his own femineity. No matter what our identity is, what face or body shape is, or how people perceive us, there is nothing more unconquerable than the human mind and its ability to think and feel for itself. Real desire cannot be changed, invented or duplicated. Hence, why particular actions are repeated by different characters in the film.

Philosophy and intertextuality aside, this is a tremendously efficient thriller, with only a few bumps along the way. There are two scenes in this film involving sexual violence that I found challenging to watch. They're harsh and unflinchingly staged. However, they are not just for cheap shock or sensationalism but eventually revealed as integral points to the narrative. Almodóvar takes his time to tell this story and tests our patience with some of these difficult scenes. Our reward is that we are provided with clarity towards both the plotting and the characters motivations. In terms of design, I liked the realism applied to the scientific elements as well. Most Hollywood thrillers throw a white coat over their scientists and they're ready to cure malaria. The scientific equipment here looks and feels tangible, which brings some credibility to the insane narrative. Meanwhile, Banderas is fairly one-note here but he remains in tune with the film's cold tone. It is refreshing to see him in something that isn't self-parodying and in his narrow corridor of brooding, he is strong enough. Although a tribute to Hitchcock this is as far from a Hollywood thriller as a film can get. It is risky, original and profound, recommended for the patient viewer.