To call Electroplankton a game would be a bit of a misnomer--there is no competition, no objectives to be met, and no points to be scored. Rather, this new project from self-proclaimed media artist Toshio Iwai is better described as a collection of interactive multimedia art installations that you can take with you. There's truly nothing quite like Electroplankton on the Nintendo DS--or any video game system, for that matter--and there are moments when it can be beautiful and completely enrapturing. But without any sort of disciplined game structure, and by relying heavily on user input--while simultaneously marginalizing it--there's not much to keep you coming back.

It's easy enough to toss around a lot of quasi-intellectual language when talking about Electroplankton, so we'll try to keep that to a minimum--instead, let's get down to what Electroplankton actually is. Imagine a set of synthesizers that you can manipulate through the familiar microphone and touch screen interfaces of the Nintendo DS, and you're pretty close. Electroplankton is comprised of 10 such musical toys, and a playful visual style is employed to give the impression that each takes place in some sort of bizarre petri dish--or perhaps a very musical aquarium--filled with different species of plankton that can produce sound and light when you interact with them.

The Tracy type of plankton come in groups of six, and will create piano tones as they retrace over lines that you draw on the touch screen. Each of the Tracy plankton are color-coded, and each color has a sort of preset pattern it plays through; but the shape of your lines and the speed at which you draw them greatly effect the pitch and the speed of each plankton. Additionally, you can use the D pad to speed up or slow down the shared speed of all the plankton. Tracy is a good introductory plankton, and it can be fun to discover the sounds that different polygonal shapes, or perhaps your own name, will produce, though it's difficult to create anything that would be recognizable as "music," and what you do create almost inevitably degenerates into a cacophony of noise.

The Hanenbow plankton like to launch themselves out of the water, creating xylophone-type sounds when they bounce off the leaves of plants growing out of the water. Using the stylus, you can play around with the angle of the leaf that they launch out of the water from, as well as the position of the leaves they bounce off of. Not only will the tones created differ depending on which leaves the plankton hit and where on the leaves they hit, but a plankton that hits the same leaf multiple times will create different tones. Because the plankton launch out of the water at a constant rate, it's easy to create progressions that overlap "in the round," which can become dizzying as you crank up the speed at which the plankton launch. Hanenbow is one of the most fully realized plankton, with several different plant configurations, and it features the closest thing you'll find to a goal in Electroplankton: Hitting the same leaves repeatedly will cause them to turn from green to red, and if you can make all the leaves on the screen turn red at once, the plants will blossom into small flowers. Festive!

The Luminaria plankton actually has its roots in "Composition on the Table," an interactive art project that creator Toshio Iwai originally unveiled in 1998. Here, four plankton sit on a grid of directional arrows. The plankton--each of which travels at a different speed and creates a different type of sound--will follow the directions that the arrows point, generating a specific tone every time they pass over an arrow. You can change the direction of the arrows simply by tapping them, or you can affect the direction of all the arrows at once using the D pad; if you want to make things a little more random, you can press and hold on an arrow with your stylus and it will begin spinning on its own automatically. You can create some pretty intricate patterns with the Luminaria, though it feels oddly limiting that you can rotate the arrows only clockwise.

Of all the plankton, the Sun-Animalcule type seems the most like an actual microbiological creature. Tapping the touch screen will cause very tiny plankton to appear and start pulsing with light and sound at regular intervals. Like the Tracy plankton, the Sun-Animalcules will create different sounds depending on their placement on the screen, as well as on the patterns in which you place them. After they're placed, the Sun-Animalcules will start to grow, and the sounds they create will very gradually shift, until they reach a certain size and pop.

The Rec-Rec plankton works like a four-track recorder that loops every four beats. Four fish-like plankton scroll across the screen while a drum beat plays in the background. Tapping a plankton will cause it to record whatever sounds the microphone on the DS can detect over the next loop, after which it will immediately begin replaying those sounds. The Rec-Rec plankton is far and away the most functional in Electroplankton, and the sorts of musical patterns that will emerge when you layer seemingly random noise is genuinely amazing. The compelling sounds that you can create with the Rec-Rec make it all the more unfortunate that you cannot save any of your work.

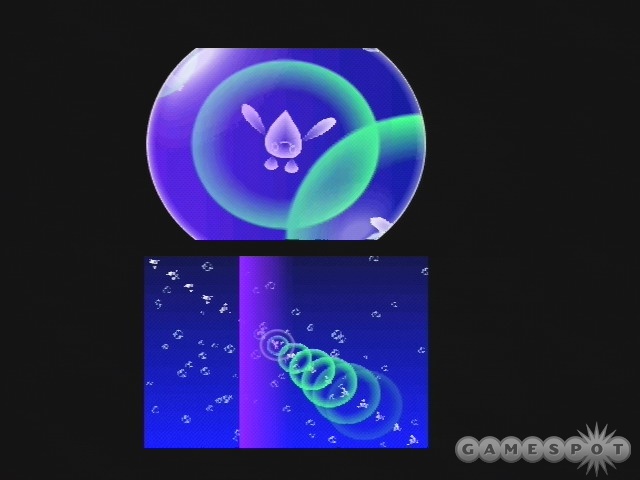

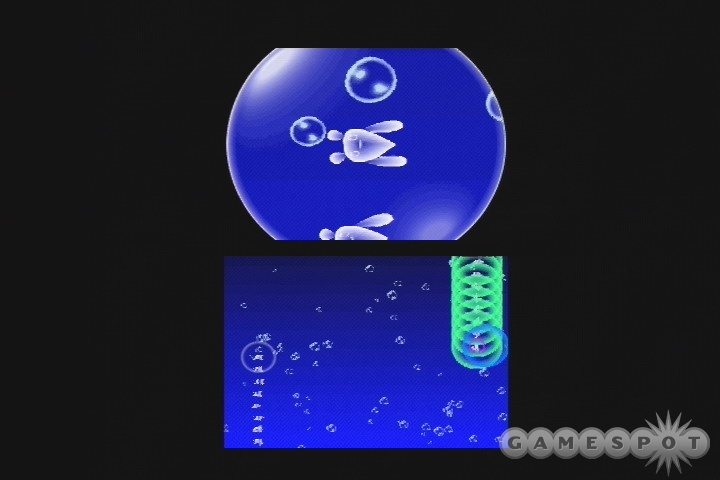

While some of the plankton in Electroplankton are standard synthesizers that have been thinly veiled with strange interfaces, the Nanocarp seem mysteriously autonomous. Left to their own devices, these tiny winged plankton will swim around the screen, occasionally producing small tinkling sounds. Tapping the screen with the stylus creates a concentric wave that will trigger any Nanocarp that get caught in it, and pressing on the D pad will cause similar waves to wash across the screen. But what's more interesting is the way they react to sounds you create. Clap once and they'll snap into a circular configuration; clap twice and they'll form a straight line. They'll also react to your blowing into the microphone or singing specific melodies, and if you master the techniques, you can actually design some simple animation routines. The manual actually lists all of the different shapes you can trigger, which, unfortunately, is a missed opportunity to add an exploratory aspect to the Nanocarp.

The Lumiloop plankton is the biggest one-trick pony in Electroplankton, consisting of five hoop-shaped plankton that will start to glow and emit constant tones when you "spin" them. You'll get slightly different sounds and colors depending on whether you spin the Lumiloops clockwise or counterclockwise, and you can cycle through a few different sound sets, but there's not much experimentation to be done here, and the novelty wears out quickly.

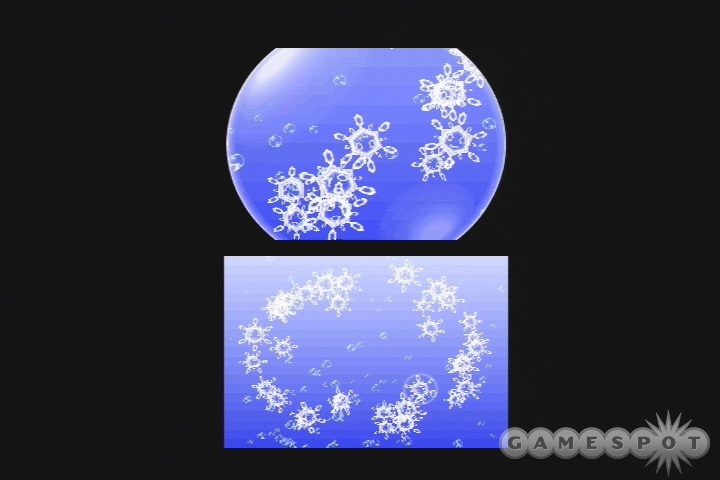

The snowflake-shaped Marine-Snow plankton start off in an evenly spaced formation of 35, with each plankton producing a different note when tapped. This orderly field quickly devolves into chaos, though, as each plankton switches positions with the plankton you tapped previously. It's not the most practical plankton in Electroplankton, but it does serve as a good example of the relationship between order and chaos. Similar to the Lumiloop plankton, though, it doesn't age well.

While most of the plankton actively avoid game conventions, the Beatnes plankton fully embrace the musical stylings of old 8-bit NES games. Five chainlike plankton fill the screen, each of which will produce a different short synthesized sound when tapped. The individual "links" in the chains represent a different note in the scale, while the tops and bottoms of each chain produce different recognizable NES sound samples. Right when you start playing with the Beatnes, the classic Super Mario Bros. "invincible" music starts looping, and any notes you trigger on the chains will start looping back with the background music at four-beat intervals, letting you build up some fun and rather complex rhythms and melodies. Aside from the SMB theme, there are three others to choose from, including a Kid Icarus theme. Beatnes is the plankton that most people will be immediately drawn to, and by providing a recognizable musical base to build upon, it's easily the most accessible, though it suffers the same limitations of the Rec-Rec plankton--you can't save anything you've produced. Even worse, after looping a few times, any patterns you've entered will just stop playing altogether, forever lost.

Finally there's the Volvoice plankton, which starts off as a big gumdrop-shaped plankton. Tapping on it will make it record up to eight seconds' worth of sound. You can play it back straight-up, but things get really interesting when you start selecting from the ring of different shapes that encircle the Volvoice, which will change the shape of the plankton and effect the sound of the playback. Some of them simply change the pitch or speed, while others will apply robotic-sounding filters or play back the sound in reverse.

Some of the plankton are simply better suited for experimentation, which directly correlates to their lasting value; but almost all of them are hindered by the fact that you cannot capture anything that you create. It's inherently pleasing when you create something you feel is worthwhile, and it's natural to want to share that with others, but Electroplankton is so concerned with being in the moment that this is difficult. Similarly, it's unfortunate that there are no interplankton activities. Most of the plankton don't create music, per se, but components of music. They're novel on their own, but being able to layer them within your DS could open the door for something much more magical. Though the game doesn't explicitly have multiplayer support, you could conceivably layer the sounds of the different plankton by hooking up with other players and forming a little Electroplankton jam band.

Electroplankton's presentation pretty well matches the abstract, experimental form that the rest of the package takes on. The instrument sounds, which range from very natural-sounding pianos to the rawest of sine-wave synthesizers, are all sharp and distinct, though if you listen closely with headphones on, you can hear some slightly dirty waveforms on the back ends of certain instruments. The aquatic and microscopic themes of the game are highlighted in the sound design by soothing, bubbly sounds and a nice, low orchestral hum in the main menu. The visuals, of course, are instrumental in establishing the game's overall theme, and it does so with an elegant simplicity. Backdrops filled with rising bubbles and slowly cycling colors creates a serene foundation, and the simple polygonal shapes that make up the plankton are kept from feeling too cold or alien by being plastered with little smiley faces. It's hard to call the sights and sounds in Electroplankton particularly impressive, but with so many games so concerned with being the biggest, the brightest, or the loudest, it's a nice change of pace to experience something a bit more subdued.

It can be argued that by maintaining such a level of conceptual purity, Electroplankton better connects with the academically minded crowd that would be drawn to such an exercise in the first place. Even if Toshio Iwai had succumbed to marketing pressures and included more pedestrian game elements in Electroplankton, its commercial success would still be highly dubious. That argument, however, doesn't rationalize away the isolated nature of the individual parts that make up Electroplankton, nor does it account for the inability to capture whatever fleeting moments of creative genius you might experience. Electroplankton is bold and uncompromising, but it still comes out feeling only partially realized.