Spyro, the purple pygmy dragon, made his fiery debut on the original PlayStation, among the surfeit of 3D platformers populating the 32- and 64-bit eras. Aside from its unique protagonist, who hailed from the opposite side of most fantasy-setting confrontations, Spyro the Dragon strictly adhered to its genre's formula, managing to be very successful in the process. Spyro's 2002 outing failed to re-create that success. Those who endured the horrid Enter the Dragonfly will be pleased to learn that VU Games has, this time around, endeavored to bring its rambunctious reptile up to something resembling modern technological standards. Despite improvements in every conceivable area, though, Spyro still never manages to hit his stride, probably because he's constantly being interrupted by a peanut gallery of supporting heroes. The Lilliputian lizard, when not avoiding outmoded platforming obstacles like bottomless pits, acts as a hollow vehicle for choosing which character-driven minigames to play. Spyro's newly expanded roster doesn't manage to save A Hero's Tail from monotony, and even the title's targeted younger demographic will probably soon tire of the game's reliance on boring collectible gathering.

No one is going to buy Spyro: A Hero's Tail for its story, which hardly bears mentioning. Red Dragon, the Dragon Elders' contumacious castaway, is staging a violent coup d'état, rallying to his standard a team of what appear to be ogreish Roman legionnaires. Another point of interest is Red's use of "dark gems" to pervert the land and discourage Dragon Elder loyalists like Spyro. You'll spend the majority of your time hoping to stumble upon these spirelike structures, so that you might shatter them, and with them Red's plans of autocracy.

As if large-featured humanoids in light armor didn't pose enough of a threat (though, actually, they don't), Big Red has several spicy boss characters on his payroll. These guys are total jokers. After some perfunctory wailing and smashing--which largely amounts to posturing--each boss will somehow start reeling from his or her own attack. For example, Inneptune, who is an unapologetic rip-off of The Little Mermaid's corpulent villain Ursula, attempts to thwart Spyro by spewing some manner of bodily fluid at him. This process so exhausts the mermaid that she must afterward cease fighting for a period of about 10 seconds. During this time, Inneptune makes a great show of exposing her gem-imbued underbelly, which can be rammed to inflict damage. If Inneptune manages to actually hit you, she'll be so taken aback that she'll have to cease attacking and expose that fleshy underbelly again. To make things all the more facile, Inneptune, like her compatriots, declares defeat three times--once for each third of her health bar depleted. The game saves your progress every time this happens, and, in the unlikely event that Spyro is killed, you'll restart your fight from one of these points, complete with full health. Suffice it to say that these boss fights are simply ego-padding interludes between gem-destruction missions.

Generic enemies actually often require more-strategic assaults than their superiors. Over the course of the game, Spyro will earn three additional elemental breath attacks, to complement his staple fire-breathing, as well as moves like improved ground-pounding. Different baddies respond differently to these maneuvers, and you'll have to experiment to see what works best. Crabs illustrate this point well, as they're really vulnerable only to electric shock. This kind of combat is standard Spyro fare, save for the water attack that A Hero's Tale introduces.

If you haven't already figured out that combat takes a backseat in Spyro, it does. Your breath attacks are used to solve puzzles as often as they are to ice, burn, shock, or hose thugs. During large stretches of gameplay, you'll hardly attack at all, instead working on double-jumping your way over frustrating platform puzzles. The design quality of these puzzles is extremely variable. In certain areas, it'll be immediately clear where you need to leap. Other settings, like the detestable Cloudy Domain, are marred by labyrinthine layouts, giving players no direction. At several points in Cloudy Domain, we had to use collision-detection problems to our advantage, to reach certain platforms that seemed to be just out of double-jump range. Faced with the choice of using nontraditional objects--like a decorative sconce--as jumping platforms, or not completing the game, we looked askance and hit the sconce. This type of design oversight repeats itself throughout A Hero's Tail, whose puzzle and level layouts aren't particularly inspired anyway.

In fact, you'll be backtracking through previously explored territory constantly, looking for that one gem you missed, but absolutely need to advance. While exploration is an important aspect of any three-dimensional platformer, Spyro doesn't inspire that feeling of awe elicited by the expansive environments found in the best games of the genre. Instead, it gives the sort of sinking feeling associated with not being able to relocate that previously unreachable item.

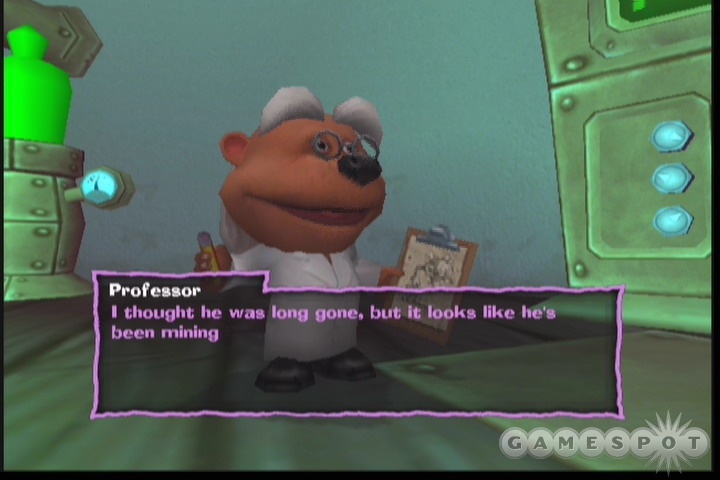

Contributing to the problem is the game's ridiculous map system, which offers nothing more than a topological overview of the landscape with shading to represent where you have and have not traveled. The only other marks on the map show your current location in the game, and those of item shops, owned by the smarmy Mr. Moneybags, an anthropomorphic bear whose Franco-Arabic accent and ethnic garb mark him as a product of colonial Algeria. This minimalist map is rendered even more useless by the fact that you have to leave the game screen to view it. In order move from point A to point B, you'll have to repeatedly go to the map screen and ensure that the dot representing your location has moved in the right direction. Furthermore, there's no single "world map." Each region is assigned its own little diagram, and unless you've used one of the game's teleport pads, you'll be left guessing how to move between them.

Putting the gameplay issues aside for the moment, as mentioned, A Hero's Tail's graphical presentation is leagues beyond that of its predecessor, and much better than the title's gameplay truly merits. The game looks the same on all three consoles, running at a steady clip and featuring bright, clear texturing that makes Spyro's turf look like Disneyland--a good thing for this pastel-pigmented platformer. All the playable characters and major non-player characters have received the high-poly treatment and look sharp as a result. The in-engine cutscenes really demonstrate the fine work that went into these models. Less care has been taken with your typical baddies, who look slightly blocky, but in a stylized way. The game's camera can be inconsistent, but it rarely gets stuck behind objects, and can, in any event, be controlled using the right analog stick. In short, Spyro's graphics hold up when compared with other multiplatform offerings in the genre.

A Hero's Tail's audio makes just as solid a showing. The music is always up-tempo and appropriate, and the characters are all well voiced, particularly Sgt. Byrd, a rugged jetpack pilot with an upper-crusty British accent. When Spyro first encounters Byrd, he's cautioned, "No Spyro. Only birds and air-force pirates can get up there--and I just happen to be both of those things!"

Although Spyro's production values have shot up, its gameplay has remained more or less the same since the series' 1998 debut. Back then, players lacking Nintendo 64s didn't have too many good 3D platformers to choose from, so Spyro's gameplay foibles were acceptable, in light of its uniqueness. The novelty has worn off. Today, modest improvements on this tired formula, like giving Spryo's once-vestigial, T-rex-like arms the ability to grip ledges, just aren't enough to make the game feel innovative. Filling the title with disruptive and boring minigames to artificially increase play time apparently wasn't a good move, either. Despite all the new window dressing, Spyro: A Hero's Tail is the same game you played six years ago, and you probably remember it being better.