about this gAME

SOUNDS: Very groovy soundtrack with a full mix of original songs.

CONTROL: Clumsy, frustrating, not what they should be.

+ Wide range of silly gadgets. Clever mix of dry humour.

- Lacks intensity.

The 1960's produced an incredible number of James Bond rip-offs, from the blatantly obvious (Operation Double 007), to the blatantly bad (Agent For H.A.R.M.), to the incredibly inspired (The 10th Victim), each a different attempt to cash in on the bond formula by adding in a higher dose of fashion frivolity, groovy tunes, and ridiculous gadgets.

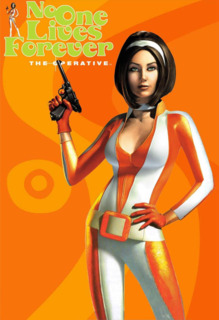

The result was a whole new sub-genre of secret spies running around in go-go boots, tight-fitting cat suits, neck scarves, and psychedelic prints. It's this universe, not James Bond or Austin Powers that No One Lives Forever borrows from, placing gun firmly in cheek for a very dry, campy adventure that knows just how ridiculous it is, and is smart enough to have fun with it.

The game plays out like a movie, complete with a title sequence, scripted sequences, and game missions that are divided into "scenes", together helping to form up a cinematic story. It stars Cate Archer, a Scottish minx recruited by the British division of an international spy agency called U.N.I.T.Y.

As a minor agent, she helps out with administrative jams while the division's league of male agents take all the risks in operations against S.M.E.R.S.H. and other secret world powers. But the latest development changes all of that.

A new criminal organization calling itself H.A.R.M. has somehow infiltrated U.N.I.T.Y.'s ranks and is using the leak to systematically assassinate the company's agents. It's when half of the male agents are dead that U.N.I.T.Y. decides to promote Cate Archer, its first female agent, to the field in the hopes that she can help uncover the enemy organization and put a stop to its killing spree.

No One Lives Forever is a first-person shooter, one that enjoys a dynamic of stealth, of going from room to room, corridor to corridor, from mini-shoot out to mini-shoot out. The intensity isn't as high as with more open battles of multiple enemies, but the intrigue is always there as the confrontation you'll find behind each corner will always be a little different.

Sometimes you'll be attacked from above, others from behind, often from some hidden place which will have you scanning the room for the source of hurt you're suffering. Literally you can aim and shoot at the horizon, and similarly be shot back from the same distance, which adds the perfect dimension of being able to shoot first from afar and then close in for tight duels. But at the worst, you're only fighting a handful of enemies, and I should make it clear for action fans that in that respect it's not a game dripping in adrenaline.

The fun is a mix of exploration, simple puzzle-like situations, and a shooting gallery-like exchange of weapons fire. It's the goofy charm of the game's theme that gives it such a fun flavour. Having a secret agent commit acts of stealth in click-clacky high heels may be implausible, but it's not that Monolith isn't aware of it, in fact they've worked it into the game's mechanics, asking players to learn to walk carefully or tip off the enemy with a poorly chosen wood floor path over carpet.

The downside is an expected one. The PlayStation 2 is not a system that embraces the dynamic of a first-person shooter easily, and although Monolith has done their best to create a comfortable compromise, it's nowhere near what the original PC game offers.

The difficulty comes in the PS2 controller's accuracy. The analog thumbsticks can only point to within a generalized location while a PC mouse can pinpoint to a specific pixel. To try to approximate that level of accuracy, Monolith has made a few adjustments.

The first is the option to adjust the sensitivity of the game to the thumbstick's movements. It's like being asked if you would like to be more or less drunk in your movements, not a real solution at all.

The second adjustment is to give the on-screen reticule, the cursor you aim with, a magnetic auto-lock ability. The result is that you only have to aim in the general vicinity of an enemy agent and the reticule will automatically lock onto his/her body for you. It works, but it also takes away some of the game's sense of challenge.

So to further adjust that, Monolith made it so that each enemy character is divided into body sections; the head, torso, arms, and legs. Only a headshot will quickly take out the character, while the torso will need several shots before there's an effect, and you can shoot all day at an arm or leg and do nothing.

Once you lock onto an enemy character, you'll find the reticule has snapped to one of these body locations. To change to a more desirable one (the head) you use the right analog stick to move it up and down the enemy target, from arm to torso to leg.

Sadly, its not a system that always works. Especially on long distance targets, which because of the pixelation of the graphics may not always be easy to see, it can be difficult to get that reticule to quickly move up to the head, if at all. The enemy are always good shots and you can be sure to be hit while you fumble with the aiming.

In several of these shoot-outs, it's your higher health and capacity to wear body armor which allows you to survive, not your ability to out shoot. It depends how much of a fan you are of the genre, if you've never played a first-person shooter before, you'll learn the controls and cope with them just fine, but if you're a hard core fan, you'll be frustrated at the number of times you'll lose when with a mouse in hand you would have won.

Much like Her Majesty's Secret Service, U.N.I.T.Y. has a tech division, one they refer to as Santa's Toy Shop that offers up a wide variety of weapons and goofy devices throughout the game. Sunglasses which double as a spy camera, a powder that dissolves human corpses, a zipcord belt buckle, and even a robot poodle which can seduce enemy soldiers, all help the game to have fun with itself and offer up fresh gameplay alternatives to the shoot outs.

Some levels will ask you to snap pictures of enemy documents, others to find and activate a series of explosives, sneak past a specific counteragent, or take part in a ridiculous exchange of code phrases.

The humour of the game really comes out in these sections, that and several sub-scenes played out by neutral characters, such as the Raiders of the Lost Ark nod in Morrocco with the conversation of a monkey and a date.

In one sniper mission, you're given the task of protecting a man who's deaf and half blind and who believes that all of the would-be assassins falling under your careful aim are street vagrants sleeping in his path. This clever mix of serious action with a counter commentary of silly happenings is the game's biggest asset and the main reason to chose it over other games and to push on towards the finish. The villains, by the way, become more outrageous the farther into the game you go.