Although it features some clever puzzles, repetition and a lackluster story mar the presentation.

At first glance, Trace Memory is identical to all the puzzle games that have come before it. The chief difference with this game is, naturally, the fact that it’s on the Nintendo DS. With its dual screen and touch screen technology, this game is able to carry a number of new types of puzzles. Now, you can pick objects up to throw them, drag them, turn them, or twist them. Rather than painstakingly copying down random drawings, the top screen often provides you with a vital clue to solve the puzzle on the bottom screen, and there are even some puzzles where you have to use the microphone to “blow” an object around. The sheer variety of puzzles is pretty impressive. Unfortunately, the game itself is not, as Trace Memory suffers from trying to make itself too clever.

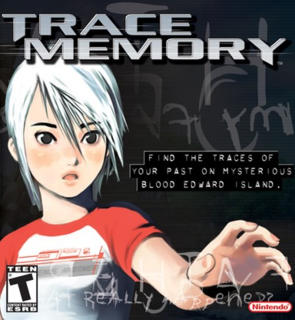

The game opens with a boat approaching the shores of Blood Edward Island, an island dominated by a large and abandoned mansion and an air of mystery. As the game’s slow-paced back story explains, your protagonist, Ashley Robbins, has been summoned to the island when she receives a letter from her father Richard, presumed dead for a little over ten years. The letter doesn’t say much, doesn’t even apologize for the whole being dead thing, but it does say that her father wants to spend Ashley’s fourteenth birthday with her on the scenic Blood Edward Island. Along with the letter, she also receives a strange machine that looks suspiciously like a Nintendo DS. This is the Dual Trace System (DTS), which is somehow coded to Ashley’s fingerprint so that only she can use it. During the game, you’ll find little cartridges scattered about that you can load into the DTS and read Richard’s journal. In addition, the DTS can take pictures, which is very useful – and often necessary – in solving a number of puzzles. It turns out that Richard is a scientist who specialized in memories, and as the game begins, it seems as if Richard abandoned his daughter so that he could focus on his studies. At any rate, Ashley arrives on the island with her aunt in tow, and quickly winds up becoming separated from her, in typical puzzle game fashion. Ashley tries to find her aunt, and in the process discovers a ghost named D, who has lost all the memories from his former life. He’s somehow convinced that Ashley can help him recover these memories, so he follows her around to offer advice about how to get through the mansion.

These opening sequences do a great job of setting the pace for the game, which is frustratingly slow. The opening cinematic sequence is filled with slow scrolling text that you can’t forward through, and the following dialogue is filled with repetition and wild leaps of logic that will make your head spin. For instance, when Ashley asks her aunt about the DTS she received, her aunt claims she doesn’t know anything about it. She then mentions that only Ashley can use it because of the fingerprint recognition technology it’s built with. The game gets more frustrating as it plods along. A typical exchange goes something like this: Ashley finds a card with a letter from her father and reads it. D asks her what she’s found, and Ashley reads the letter again. Or, Ashley will be thinking about something, and D will ask her what she’s thinking about, so Ashley tells him. Often verbatim. If that repetition wasn’t enough, at the end of every chapter you have to take a little quiz to remember the details about what you’ve discovered, ostensibly so that Ashley doesn’t “forget” what’s happened so far. There also a lot of needless backtracking involved in untangling this mystery. Most puzzle games have you chasing clues all over the place anyway, but Trace Memory adds a whole unnecessary leg into it. Whereas most puzzle games allow you to accumulate a number of random items before you need them (often allowing you to pick up items you don’t even need), Trace won’t let you pick up any items until Ashley is extremely confident that she needs it. For instance, in a storage room outside the mansion, you’ll find a box of iron spheres. The gate to the mansion is locked by a pair of hand statues, one of which is holding an iron sphere. Just looking at the puzzle, you’ll realize what you need to do, so you may go back to grab a sphere right away. Easy enough, right? Unfortunately, Ashley won’t agree with you. If you try to pick up a sphere, the game notifies you, “The box is filled with iron spheres of various sizes.” Why would you want one of those? You’ll have to return to the gate, look closely at the hand with a sphere, and then closely at the one without until Ashley realizes, “This is the one . . .” Oh, hey! One of these things is not like the other! Now you can get the sphere, return to the hand and then solve your first real puzzle – tossing the sphere up into the hand, making use of that good old dual screen technology.

Later on, this trait becomes even more obnoxious. In another room, you’ll find a notepad that had something written on it before the top sheet was ripped away. It’s easy enough to figure out how to solve this puzzle, especially with a nearby pencil to give a clue. The pencil breaks, however, leaving you to find something else to rub on the impression. Luckily, there’s a fireplace nearby. Now, if you wandered over to the fireplace first, you wouldn’t have been able to find anything except for some charcoal, which of course you couldn’t pick up. Who would need that? However, if you return after breaking the pencil, Ashley not only picks up the charcoal, but mentions to D (who remarks that he doesn’t see why she’d EVER need that) that “Hey, you never know when this may come in handy.” That line wouldn’t be nearly as aggravating had it come BEFORE you knew you needed it. This is just one example of Trace Memory trying to be a little bit too clever for its own good.

The puzzles are the other prime example. As mentioned before, Trace Memory throws a wide variety of puzzles your way. Not only is there the traditional slide puzzle sequences, piecing old documents back together and swapping books around to form words, but you’ll also be able to throw items about, use the dual screens to create a reflection (in a puzzle of pure genius!), and take rotate your pictures around to reveal secret clues. It’s almost as if Trace Memory was designed to show all the really cool ways the DS touch screen could be used, without realizing that WarioWare had already done that very thing.

If you can scrape up the endurance to get through this rather brief game (it shouldn’t take more than six hours to wrap it up, and that’s if some of the puzzles stump you), there’s not much to call you back to it. For one, you’d have to sit through the tedious sequences again, and the puzzles don’t change at all on a second playthrough. There are a few different endings you can get, but these mostly hinge on finding squirreled away items or revealing more of D’s memory.

In my opinion, this is a game best avoided. If you want to see what the DS is capable of, grab a copy of WarioWare and at least have fun doing so.