It is not often that a game can be made based on real-life history or current happenings without being seen as a mockery and/or exploitation of the latter. The Tropico titles are not such games, but while they may be a mockery of actual banana republics (among other kinds of stereotypical third-world autocracies), Tropico is far, far from being cheaply and tastelessly exploitative.

In fact, the Tropico games were known for surprisingly sophisticated gameplay that also happens to tap into the glamour and megalomania of being a virtual dictator, thus delivering a gleeful experience.

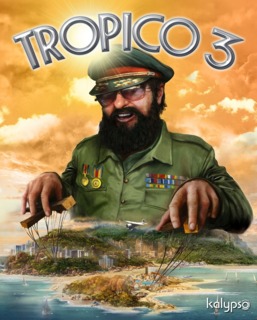

Tropico 3 continues this series' tradition and more. The latter impression can be had as soon as a Tropic veteran launches the game; Tropico 3 have ventured into the realm of full 3D graphics, which is a departure from its sprite-dependent predecessors.

Like Tropico 2, Tropico 3 is a revamp of its predecessor. In addition to the complete graphical overhaul, there are also gameplay changes, some of which are deliberately and unwittingly made possible via the 3D engine and some design liberties-cum-conveniences that the developers, Kalypso Media, had taken.

As in the previous games, the player takes on the role of the leader of a banana republic, specifically its President, during the Cold War era. He/She will have to manage the economic and social well-being of the island that he/she governs (and which is always named "Tropico", regardless of the scenario's circumstances); the player will have to juggle the happiness and political satisfaction of its inhabitants as well.

This is where the many mechanics of the game come into play. The first-most is, of course, the mechanic of issuing decisions/directives.

The player has control of a camera that is ever looking at the island; it is constrained to a down-turned hemispherical orientation. The player will have to be looking at a relevant object in the game and select it before the options that the player wants to consider can appear in the user interface.

In other words, there are very few tabs, windows or panels that the player will use to make sweeping decisions on policies. This is usually a dubious design if the graphical designs of the game are incapable of directing the player towards said relevant object, but the developers have invested commendable efforts into helping the player spot these objects.

Furthermore, the player can also set and use hot-keys to select a specific kind of building without having to look at it, or if the player has clustered important buildings together, bind a hot-key to send the camera over to this location for quick selection without using keyboard shortcuts. (Keyboard shortcuts do require some finger-work across the keyboard, which some players may not favour.)

(It is worth noting here that Kalypso appears to have considered the concerns of players who are averse to clustering important buildings together, which may render them vulnerable to collective destruction, i.e. an "all eggs in one basket" situation; with the exception of certain scenarios, there are few unfortunate occurrences in which buildings that are clustered together can be destroyed in just a single stroke of misfortune.)

If there is a flaw that is less forgivable about this game design, it is that the player is not able to make any decision about certain policies until their associated buildings have been built; the default settings of these policies will be active until the player has made it so.

For example, policies on immigration are not available for tweaking before the Immigration Office is built; meanwhile, the policy is set at a default, which is an average influx of refugees. Considering that the population of Tropico is both the player's most important asset and also the greatest source of trouble, the player may want to control the influx right from the start of a session; unfortunately, there just is no such chance.

On the other hand, the policies' default settings also lead to less potential trouble. In other words, having new options to alter policies with also mean that there are new consequences that are associated with said options. Drawing on the example of immigration again, the Nationalists would not have a problem with the default immigration influx, but having built the Immigration Office, this party will clamour for nothing less than a complete closing of Tropico's doors.

The second main mechanic of the game is money, described in-game as the most important thing to a despot. Money that the player can use is contained within the treasury of Tropico, though this is by no means the personal stash of the player character - at least, not yet.

There is no tax system whatsoever to take money from the populace of Tropico and have it go into the Treasury at regular intervals. This is a marked difference from other games at the time, though considering that the people of Tropico can be quite willful enough already, a tax system would have made them even more difficult to manage.

On the other hand, there is still a regular injection of money, though it only occurs yearly in the form of financial aid from the two superpowers during the Cold War, which are the USSR and the USA. The amount of aid received from either superpower is dependent on how satisfied the superpower is with the player's efforts. If the player had been embracing populist and socialist ideals, and keeping the Tropican Communists happy, the Soviets would be happy. Likewise, if the player had been investing in education, encouraging liberty and keeping the Capitalists happy, the Americans would be happy.

If the player fails in sucking up to either, they will be sending warships to Tropico as a warning, and if they are pushed far enough, they will invade, leading to a straight game-over.

Often, what placates one angers the other, but there are ways to please both at the same time, and finding these can be quite fun. However, once the Tropican treasury has reached sizable levels, the aid will stop coming; the game does not seem to inform the player of this game design, unfortunately, though players who know about the real-world purpose of aid to Third-World nations will understand why the aid is cut off.

Furthermore, regardless of how well that the player is sucking up to the superpowers, there is only ever a ceiling of $6000 in aid from each superpower (in most scenarios), so additional money has to come from elsewhere.

The other means to gain money can be mainly grouped into three categories, depending on their primary sources: the first sorts are through the Tropicans themselves, the second through the export of Tropican goods and the third through tourists. There are some other means, but these are often scenario-dependent or through special events.

Tropicans get free food, religious services and healthcare, among other privileges (assuming that there are such services or goods to be had in the first place, that is). Accommodation is not free for them though, as all land in Tropico is considered property of the state, so the rent that Tropicans pay will be a reliable source of money, assuming that they have the jobs and income to pay for them, of course.

However, accommodation is not enough to squeeze the money out of the Tropicans. To convince them to part with more of their cash, the player will have to build places of entertainment, which not only appease their desire for leisurely activities but also allow the player to set the fees that they will be charged with.

Many of these entertainment buildings are, interestingly, not just build-and-forget facilities. In addition to setting their fees, the player may also be able to select their service quality and even options to restrict the kinds of customers that they will have (especially restaurants). All these options generally lead to changes in service quality, which will be the main factor of attraction, and the maintenance costs of said facilities.

Even veterans of city-building games would be surprised at the versatility of the money-making facilities that can be built. For example, using the example of the most basic of entertainment structures, the Restaurant, it can be set to receive Tropicans from all walks of life, so the fees charged has to be low, in return for a very reliable if rather average rate of income; conversely, once Tropico has a high-income populace, the player may choose to build more Restaurants, but configure these to cater to very rich customers instead by choosing options that restrict access to the common folk in return for a significant increase in service quality.

There are plenty of entertainment buildings that can be built, but many of these have the fun occurring indoors, i.e. customers merely enter the buildings and have their models disappear temporarily. There are some more impressive ones, like the Stadium and its animated sports events, but these occur so late into a session before a player can unlock and afford these that by the time, the player would be too busy to appreciate their aesthetics and animations.

Regardless, the player will have to build these to increase the entertainment rating of Tropico, as well as improve the tourism rating of the island as well. (The game does inform the player that tourists value these buildings as well, fortunately.)

Of course, for Tropicans to have the money to go to these, the player will have to create jobs through the other two sectors of income (though the entertainment sector also creates jobs on its own, especially ones that conveniently require low qualifications).

Most players would probably soon realize that the industrial sector is the most potentially lucrative, but not the most reliable or steady. This is partly because Tropicans can consume their own locally produced goods without any charge, so to gain income from these goods, the player will need to export the surplus that remains after the Tropicans have taken their share.

The export markets are simply represented using a list of prices for the goods that the player can make during that scenario. This list helps the player a lot in planning on what goods to produce, but it also takes away any surprise to be had from expanding into the industrial sector. However, certain scenarios will have yet-to-be-encountered goods added to the list, or even prices of certain goods completely sky-diving (though the game can never completely remove a type of goods off the list).

The export markets can fluctuate wildly, though one factor is for certain and within control of the player: the more units of one type of goods that the player exports, the lower its price gradually becomes as supply fulfills demand; the game does inform the player of this basic economic mechanic, fortunately. On the other hand, the player is not really given many options to control the supply of Tropican goods to the export markets, other than to demolish and build the associated industrial structures as needed.

Farming is the first segment of the goods-producing sector, and it is one where its goods are certain to be in demand, being (mostly) foodstuffs after all. There are quite a handful of crops that can be planted, each of which has its own soil requirements and appropriate graphical designs.

It should be noted here that the different soils are already hard-coded into the map in play, i.e. their suitability for certain crops will not change regardless of whether their terrain topographies have been altered or not. This would be disappointing, if the player actually has officially-included capabilities to alter the topography of the island as he/she likes, but there isn't any.

Farming is not the only basic foodstuffs-producing activity. There are fishing and ranching (that is, animal-rearing), which produce different kinds of food. The variety of foodstuffs on Tropico will contribute to the socio-economic factor of food quality, as do the ratio of the amount of food supplies to the population of Tropico. Furthermore, the foodstuffs produced are not to be consumed as just end-customer goods, some of them, like fish and pineapple can be sent over to other goods-producing buildings as raw materials to be added value to.

Part of the fun of developing the manufacturing segment of the industrial sector is in setting up a supply chain to buildings that produce more valuable goods and having this work efficiently, e.g. placing the source of raw materials like crop farms close to the factories that consume these.

These manufacturing buildings can create a lot of jobs, and can be upgraded to produce different kinds of goods (often more expensive versions of these), or a mixture of these (especially in the case of the Cannery). Interestingly, not all upgrades are straight upgrades; some such as the Machine Press for the Cigar Factory, turns its cigars from hand-rolled quality to machine-rolled quality, which has less value but can be produced in greater quantities. Some increase the maintenance costs of the building or increase its pollution rating, in return for some benefit.

There is mineral wealth to be gained from the island too, but like real-life minerals, these are ultimately finite. The easiest minerals to exploit are bauxite and iron-ore, which are goods that have no added-value variants and thus make for very good early-game income, if a rather polluting source of it.

The player can later exploit oil wells both on-shore and off-shore to derive wealth from the black gold. Oil-based goods are, peculiarly, the only commodities that the player can prevent from being exported in an attempt to drive up costs, though the player will have to build Oil Refineries and upgrade their storage capacities, and these are large sea-side buildings that gobble up a lot of space that could be used for other purposes.

Considering the presence of product-value-adding structures like Oil Refineries, a few material-processing structures are noticeably missing from the game, such as smeltworks for iron ore and bauxite. The game does not give any plausible reason for the omission of these structures, yet thematically in real-life, smeltworks can be found on Pacific island nations (whose leaders bothered to build them, that is). However, a wise player who has played some distance into the game would realize that this omission lets said commodities play the role of starting exports, essentially serving to jump-start the current island's economy, as has been mentioned earlier.

A tropical island won't be one without any forests or jungles that can be cut down for lumber. These are somewhat renewable resources, if the player is careful in exploiting them. Simply plonking down a lumberyard next to these are enough to obtain logs from them - and exhaust the entire forest if the player does not adopt the logging policies and upgrade options that prevent this from happening.

Logs on their own make for very poor trade goods (probably so in order to balance against their renewability and immediate availability), so the player may have to construct value-adding buildings like the Lumber Mill and Furniture Factory to prevent the logs from being wasted. However, the player will soon notice that these value-adding buildings require a workforce of at least high-school education, thus presenting inter-dependencies between the economy of Tropico and its other aspects, namely education in this case.

Goods that are to be exported will be stored at the buildings that produced them, yet they have to be ferried over to the Harbor to be prepped for export. There are no storage costs for keeping these goods at their source for a long time, but as long as they stay at their source, there won't be money coming in to recoup the costs incurred for maintaining said factories and paying the workers' salaries.

This is where the jobs known as Teamsters come in. Despite their name, they really work alone to drive trucks to and fro the island, hauling goods from factories and other sources of merchandise to where they are needed or the Harbor, to be exported.

Unfortunately, this is where some of the game's worst and most frustrating flaws can be encountered. These will be elaborated on later.

The tourism sector not only brings revenue to Tropico, but also brings plenty of colour (figuratively). Once the player has built a Tourist Dock or Airport (which will attract tourists with different spending capacities) and accommodation for tourists, they will start coming in to spend money away at any entertainment buildings or tourism-oriented facilities. Getting them to come in small numbers is easy, but getting more to come and encouraging them to stay longer is harder; a tourism rating will be a general indicator of how many tourists (and tourist dollars) that the player can obtain.

To increase this rating, the player has to expand the variety of tourist attractions on Tropico, as well as ensuring the safety of tourists and keeping pollution low. The safety of tourists are associated with events like rebels or terrorists kidnapping tourists or threats to bomb tourist attractions, and how the player resolves these will depend on the player's actions and some luck (more on this later).

The matter of pollution is a bit more difficult for the player to influence, however, as there does not appear to be any way to obtain visual information on the pollution in any location on the island of Tropico. The player can only gauge this by considering the proximity of pollution-heavy buildings and the overall mood of the Tropican Environmentalists.

Fortunately, this is just about the only serious flaw in the game designs that are intended to generate information about the island for the player to analyze and make decisions for. Other game designs, such as different sliders to control the salaries of employees of a certain type of facility, or the salaries of employees according to their education levels, do not suffer as serious a setback as this one.

While the island needs infrastructure like an electrical grid to unlock and power more advanced buildings and services like high-level healthcare to operate smoothly, the most important and most basic need is a working network of roads. Yet, while the more advanced requirements for a more progressive Tropico can be fulfilled and maintained without many technical issues, getting traffic to flow smoothly can be a huge headache and a huge source of aggravation.

Yet, the player cannot make do without a road network. Even though any island in Tropico 3 is an island, having people walk/run from one place to another can take too long for them to achieve whatever they are supposed to do.

Theoretically, all places in the island can be connected to each other using a chain of single roads, but problems affecting the AI scripting of motorists and the game designs that determine how an in-game person can get himself/herself motorized hamper this. There are plenty of such problems, so this review will only cite the ones that a discerning player will most likely notice quickly.

The first of these is that there is no actual traffic regulation that had been worked into the AI scripting. At junctions, whichever vehicle is quicker to cross will cross first, meaning that if vehicles coming from a different direction managed to cross ahead of others from other directions, the others are going to have wait until the former have all completely crossed. This can lead to serious backlogs of automobiles, and Tropicans not being able to perform what they are supposed to do.

This problem can be somewhat relieved by building critical buildings like the Construction Office and Teamsters away from areas with major hustle and bustle such as the Harbor, but this is a consideration that could have been rendered unnecessary if the game had included traffic regulation. Furthermore, the game doesn't emphasize the importance of having critical facilities away from such areas; the player will have to figure this out the hard way.

At the very least, Tropicans that are stuck in traffic for too long will eventually exit their automobiles, though their vehicles simply disappear from sight, thus giving the impression that this is a slap-dash work-around. These Tropicans will walk on foot from then on, not getting into any vehicle, thus wasting a lot of time.

They will keep walking, or keep getting stuck in traffic, at least until their work hours are up or it is sleeping time for them. In the launch versions of Tropico 3, travelling time is also included in the work hours for Tropicans with jobs; this means that if they are stuck too long in commuting hiccups, they may end up not performing their jobs at all; the player, and the island of Tropico, will also suffer the consequences that arise from this, such as goods not reaching places that they have to be sent over to in time.

The player can somewhat alleviate this by paving pairs of roads in parallel so that the pathfinding scripts of the Tropicans can have them switching lanes whenever convenient, but these scripts will always consider the route with the shortest distance traveled first, and not the route with the least travel time. This means that traffic jams can still occur anyway, with Tropicans caught in the backlog not having the smarts to quickly switch to the other stretch of road that happen to be clearer.

While every adult Tropican knows how to drive, his/her access to automobiles is not as certain, however. If the buildings that driving Tropicans exited from do not have driveways, they will have to walk over to the nearest Garage to obtain a car. (A "Garage" in Tropico 3 is a combination of a multi-story parking lot, valet and garage - which is a facility that hardly exists in first-world nations, much less third-world nations that Tropico is a rendition of.)

The player can alleviate traffic issues further by building Garages along problematic regions of the island if he/she does not want to completely re-plan the layout of the city, but this increases costs (which the Garages cannot directly recoup for) and Garages are very large buildings that take up space that could have been used for something else.

The developers could have resorted to the more convenient design of spawning automobiles close to Tropicans who wish to use the roads.

The frustrations with the Tropicans' less-than-exemplary AI are not just limited to these. Another severe complaint that can be had is that Tropicans who work as builders have very obtuse AI when it comes to reaching the model for buildings that are to be constructed. They exit from their vehicles at the point on the road that is closest to the construction site, which is alright, but more often than not, they walk towards the far side of the building site, wasting their work hours on unnecessary walking.

It is also surprising that despite the premise of Tropico being an island that is surrounded by the ocean having been around for a long time, Kalypso had yet to include other methods of transport, namely coastal ferries.

Pathfinding isn't the only issue with the AI designs of the citizens of Tropico. Outside of work, i.e. activities that do not contribute to the prosperity of the island, they do a lot of things, as one might expect of citizens in an otherwise normal banana republic. However, an especially frustrating activity that they frequently do is to loiter about aimlessly - even if there are distractions worthy of their spare time, such as entertainment, religious fulfillment or just going home to rest.

There are also activities that could have been left out of the game or at least automated in order to streamline the behavior of citizens, such as going to the marketplaces or food-producing buildings to collect food for their families.

Fortunately, the other mechanics that do not involve fussing around with physical matters like the mechanics of traffic and transfer of goods are a lot less frustrating, and also a lot more fun.

One of these is the creation of the player character. The president of Tropico exists as an actual in-game character instead of a disembodied leader.

The player can make choices from a set of appearances for the character, many of which are inspired by the fashion sense of real-world leaders, with Fidel Castro's beard being especially prominent. Of course, these are just cosmetics, and unfortunately, they are difficult to appreciate as the gameplay will require the player to zoom so far out that the President is barely visible most of the time.

The other aspects of the President are easier to appreciate. The player can select the background of the President from a list, most of which usually grant benefits that would be of great help to the player. Then, there are traits, which generally grant benefits in exchange for nasty penalties. Many of these personality and history choices for the President have very amusing descriptions, which can make character creation a joy, if a brief one.

The President has a human-sized model, and one of many that will be placed on an island that is many times its size. Luckily, Kalypso had considered that the President's in-game model will be too small to manually select, so there is a keyboard shortcut to select the President on-the-fly.

Despite being seemingly human, the President is practically an immortal character that is incapable of growing old, getting sick or dying from being wounded. If the President is ever caught in battle and is outmatched, he/she will "strategically retreat" towards the nearest building. While there will be events like terrorist bombings and assassination attempts targeted at the President, he/she can never be truly slain; the price for failing in these events is that the President's presence in Tropico is suppressed, due to reasons like recuperation or simply going to ground.

The President is the only Tropican that the player can control; the others have a will of their own. The player can send the President over to other places on the island, and he/she will decide whether he/she should hoof over on foot or get to the nearest garage to get his/her limousine depending on the distance that has to be travelled.

Having the President enter service-rendering facilities increases the quality of these services temporarily, while having him/her enter goods-producing buildings increases productivity; a handy, high contrast 3D icon floats above such structures to indicate the bonuses are in effect. These are potent bonuses, as the player can exploit the President's skill in various ways, such as boosting the service quality of High Schools or Colleges so that they produce graduates faster. Therefore, it has been balanced with a short but still significant delay in between the President entering the building and the bonus being applied. Fortunately, the President can be withdrawn during this time, if the player needs him/her to be elsewhere.

The President does not just stand around doing nothing if the player has not ordered him/her to do anything; he/she will automatically wander around the immediate vicinity, searching for facilities that he/she can get to in order to do whatever he/she can do to it. However, the President is not smart enough to move elsewhere on the island if the immediate vicinity is empty; in this case, he/she just loiters around, which can be a disappointing AI design.

While the management and development of Tropico (or its plundering and ransacking) can be considered to be a competent (if rather mocking) emulation of that for a banana republic, it has slight deviations from its real-world counterpart, mostly due to gameplay designs that are intended to make the game more convenient to play.

An example of odd game designs can be found in that for Army Bases. While they understandably act as housing, healthcare and training facilities for soldiers, they do not open up the job of a soldier for Tropicans who want to pursue a military profession. Instead, the player has to build Armories and Guard Stations in order to attract potential soldiers and generals. On the other hand, it does somewhat make sense as soldiers would not want to sit around in bases and loitering around waiting for action - though they will still loiter around when they are not on-duty.

Examples of game designs that can be considered convenient at a glance include the absence of any storage limits for goods, other than hoarded oil (as mentioned earlier), the consideration of infant/minor Tropicans as being attached to pairs of adults instead of being considered fully-fledged Tropicans for purposes of accommodation - regardless of the number of the children that this couple has - and the Market building automatically generating the food that Tropicans need (though the island's food quality rating is not affected by the number of Markets there are), among other design conveniences (some of which had been mentioned earlier as well).

The most powerful tools at a player's disposal are Edicts. These are categorized under self-explanatory categories like social, foreign and economic policies, and can be enacted by paying the necessary costs. These Edicts are usually beneficial, such as education policies that greatly increase the rate of graduation in High Schools and Colleges and the gaining of hands-on experience for Tropicans who are already working. To balance the power of these Edicts further beyond the monetary/fiscal costs that had to be paid for, they often require associated buildings to be built first, much like how the changing of policies are designed.

Technically, Edicts are a form of policies and so perhaps their being subjected to the same kind of designs would be acceptable, but as has been mentioned earlier, such restrictions that require associated buildings to have been built can be rather stifling.

Being a game that mocks corrupt regimes, there is an option for the player to embezzle from the island. All expenditure of treasury funds are for the player to decide, but by default they will be expended in the interest of Tropico as a nation; the President does not appear to be paid any remuneration at all, as a consequence. Nevertheless, there are many ways to embezzle funds that are intended for entry into the Treasury, such as setting Tropican banks up as slush funds.

The money embezzled goes into a separate score category for any scenario that the player plays. Generally, the more money that had been funneled away, the more this category of score contributes to the player's total score; there are even achievements associated with this practice of virtual corruption.

Unfortunately, this game feature is only for the purposes of leaderboard races and one-upping rivals (on Steam, in this case). There is no way for the player to withdraw from the President's "pension fund" to inject some money into Tropico's own treasury when the player needs some more extra cash to make a decision that needs to be taken.

The player will not be spending all of his/her time in Tropico 3 managing and directing the island. He/she will also face random events that sometimes occur for no rhyme or (less so) reason. Some examples of these have been mentioned earlier, such as terrorist threats; others include foreign or local interests approaching the player about matters that they prefer to keep discreet, and meddling from corporations and NGOs.

How the player resolves these issues will determine the consequences that occur immediately after and some time down the road. Generally, if the player opts for the easy way out, there will be nasty consequences later, whereas the player may benefit from suffering hardship early on to reap the fruits later.

Yet, many of these events do not work out in such typical ways; a player can make a decision that cause nothing but problem after problem, from early on until the end of the scenario. Opportunities may arise from some nasty occurrences; for example, the plummeting prospects of an economic segment may also lead to drastically reduced maintenance and/or investment costs for that segment, giving the player a cheap method of generating jobs to tackle unemployment with.

Regardless of the player's choices, there are always commentary on any decision and outcome, and it is almost always hilarious to read.

Some events are not random, such as the ones in the official scenarios. These are often decided by scenario designs, such as severely fluctuating markets in scenarios in which the player can only obtain income through imports. Many of these events are also interconnected, such as one event where the player is given the option of investing in dubious schemes that may contribute to the impact of another event that will occur later, often to accompaniment of hilarious writing too.

Yet, the official scenarios may give the player the impression that taking the most ruthless or morally dubious solution is the surest way to win. There will not be any example mentioned in this review, lest it invites spoilers, but it should suffice to say that this outcome is almost always the case with taking such decisions. Tropico 3 is, of course, a game, but from the aspect of gameplay, such event designs do not encourage the player to explore other options, which have inferior outcomes and often nothing extra to compensate.

The official scenarios are designed in such a manner that the most fundamental of the economic and social aspects of Tropico are introduced first, while the later scenarios introduce more advanced gameplay like supply chains for the production of higher-value goods and luxurious services for a Tropican demographic whose income is gradually increasing.

The scenarios that are unlocked much later start with plenty of gameplay restrictions, such as the generation of electricity being off-limits and some buildings being disabled, depending on the themes and backstories of the scenarios.

These are very contrived scenario designs that are adopted to give an increased level of challenge, but fortunately, Kalypso had designed events that are centered on these restrictions. For example, there is a scenario that has the construction of a lot of high-tier buildings being restricted, but events will occur such that the player can make decisions on which buildings to make available. These events give these otherwise very typical gameplay restrictions some interesting and understandable context.

Regardless of the scenario in play, there is usually the mechanic of elections that the player will have to deal with. Despite being the great leader of a backward island nation, the player has to win elections to renew his/her mandate of power. Generally, the player can win elections easily if he/she can keep most Tropicans happy with their quality of life, which is easier said than done, but losing any election means an automatic game-over.

The player can attempt to fudge election results in his/her favor, but it only affects a small percentage of the votes. In other words, if the player has been a very, very bad President, he/she is guaranteed to be kicked out through the ballot; he/she may not choose to ignore election results, which is quite unlike certain real-world despots. Furthermore, even if he/she wins through fraud, there is a chance that his/her wrong-doing can be discovered, resulting in a massive loss of trust across the Tropican diaspora.

On the other hand, if the player is certain that he/she will lose an election, he/she can simply not hold any: this is the privilege of the President. However, doing so simply makes Tropicans hate the President even more.

Another mechanic that is certain to be present in just about any scenario is the presence of rebels on the island. These are typically made up of individuals who are fed up with the player's decisions for one reason or another, such as the President defrauding elections or refusing to hold them. Nevertheless, the most common reason is unemployment: unemployed Tropicans will have no income for a lot of things that contribute to quality of life, eventually driving them to levels of satisfaction that are so low that they are more than likely to join the rebellion.

When they have enough numbers (usually above ten), the rebels will launch occasional attacks, which become more frequent as the rebel group increases in size. They will often target economic buildings, especially the more profitable and more polluting ones, and they won't stop until the buildings are no more or they have been scattered by a counter-attack. If they are feeling especially bold (usually when they outnumber the player's own defensive forces by a huge margin), they will go straight for the heart of the player's power: the Presidential Palace.

The player always starts with this building. It may be a tough one with four soldiers (thus being the first building with military personnel), but once it goes down, it is a straight game over.

To counter rebel attacks, the player has to raise an army through Army Bases and affiliated buildings, as mentioned earlier. However, the player will have no control whatsoever over the soldiers and their generals, other than to have them staff military buildings. When a rebel attack occurs, they will respond to it in a piece-meal manner, which is disastrous if the rebels have numerical strength because the latter always spawn in bunches. If the scenario is designed such that rebels can increase in numbers rather quickly, the player will be swamped with too many rebels for the army to handle.

If this happens, then the player can only hope that the factor of luck that also play a role in battles swings into his/her favor, though it could work the other way around as well.

For other Tropicans with different professions, their skill level determines how productive they are; for soldiers and generals, theirs determine how likely they are to kill their enemies or rout them, or get killed or injured to the point of retreat. In other words, their skill levels are no more than modifiers of dice rolls, which can still go any which way.

Luck also plays a role in events that allow the player to select solutions that Tropico's secret service can enact, if the player has ordered the creation of one. Similarly, the skill levels of the player's secret agents will be used as dice roll modifiers, but these solutions can still work around in random ways, including really terrible outcomes that result in not only harm to Tropico, but the possible death(s) of the secret agents as well.

Tropico 3 is hardly a luck-dependent game, so some players may find it disappointing that the resolution of an event as important as rebel attacks is dependent on luck.

It should also be pointed out that as big as the player's army gets and no matter what policies that the player takes regarding the military (such as the military modernization edict, which does not provide the Tropican army with tanks despite what is depicted in its icon), the Tropican army cannot repel or deter an invasion by either superpower. Another thing that should be mentioned here is that policemen do not participate in battles with rebels.

Players who are hoping for more comprehensive mechanics of combat in Tropico 3 are going to be disappointed.

Outside of battle with rebels, the player's army serves more reliably. Army Bases and Guard Stations act like Police Stations do, keeping law and order in the vicinity. However, their areas of effect are smaller than that for Police Stations and they also have a stronger adverse impact on the liberty rating of the island.

As mentioned earlier, the player may be able to govern the island of Tropico however he/she likes, but cannot change the geographical layout of the island. However, the island can still be landscaped indirectly through the exploitation of a game design that was intended for gameplay convenience.

The foundations of buildings can only be placed on flat terrain, but as Kalypso had intended the island of Tropico to be a facsimile of a tropical island, Tropico has plenty of curvaceous terrain, which would severely hamper the construction of buildings. However, Kalypso has added the convenience of settling down a building anyway on terrain that is approximately flat, by altering said terrain to fit the building. The same convenience also occurs for the paving of roads.

This is a handy game design, but it can also be used to deliberately warp terrain in order to build buildings at where they are not supposed to be situated. For example, the player can repeatedly place and remove buildings near coastal areas to raise the ocean floor, just to accommodate coastal buildings. The same game design can also result in terrain being accidentally warped such that the re-paving of roads becomes virtually impossible. For example, if the player created a stretch of road down a hill, part of the hill will be raised to accommodate the road so that it is not too steep; however, if the player realizes that he/she has made a mistake and removes the road, the hill will not return to its original state and another stretch of road may not be paved onto the hill because it is no longer pristine.

(In this case, the player will have to deliberately warp the terrain until it becomes suitable for the placement of roads, which can be a huge hassle.)

These awkward exploits and flaws could have been avoided if Kalypso had included an official feature to alter terrain as the player sees fit.

A feature that has been included in the game to emphasize the selfish tendencies of despots is the player's ability to select individual Tropicans and do all kinds of nasty things on them, such as assassinate them, arbitrarily arrest them for incarceration and reeducation, or bribing them to curry favour. However, any consequences and benefits from these decisions are mainly restricted to these individuals, who are just too insignificant to matter, especially if there are hundreds of other Tropicans of the same mentality. In fact, the player would probably be better off working the Tropican economy and society to effect changes in said individuals.

Random events occur occasionally and their nature is random, as is understandable, but an observant player will notice that many of them often occur at the turn of the year, and rarely at any random time. These include natural disasters like earthquakes, market fluctuations and outbreaks of "llama flu", among other things; an unscrupulous player can attempt to exploit this by saving and reloading the game repeatedly before the turn of the year to get favourable events.

Much of the information in this game is conveyed through text. This can seem boring to players who are not into reading, but for those who do not mind, the writing can be rather amusing. Much of it consists of pokes at real-life leaders with over-the-top charisma and the megalomaniacal habits of despots, among other kinds of jabs at politicians across virtually all political spectra and witty renditions of stereotypes about Third World nations and the products that they make. For example, the description of the Cannery includes a droll comment on canned food being more expensive than their raw products.

As mentioned earlier, Tropico 3 is a fully 3D game, and it is a rather pretty one too. While Tropico 3's art palette is constrained by Tropico's status as a tropical island, the island is a believable virtual rendition of one: sandy coasts or tide-worn rocks line the edges of of the island, while its interior consists of lush jungles or grassy plains (though the animations for these are rather sparse, merely consisting of jiggle-bone swaying).

The island becomes even more interesting to look at once socioeconomic progress sets in. The Tropicans, other than the President, have models that eventually seem to repeat as they are shared among different professions, and will especially seem this way when the island's population reaches into the hundreds. However, there is a large variety of models (many of which are based on the model and sprites of previous games), and these are surprisingly well-detailed and animated when seen up-close.

The designs of buildings are mostly rectangular and boxy affairs, but like the Tropicans, they have plenty of extra details and polygons (which become apparent when these buildings are demolished for whatever reason). No two types of buildings ever look alike too, which is a game design that adds visual variety to the aesthetics of a developing city-island. There isn't much animation to be had from these buildings, though this is perhaps expected of Third-World structures.

With its setting being an ocean-bound island, Tropico 3 has models and animations for ships and other naval vessels. These are appreciably well-scaled compared to land-based objects, and move across the rippling waves of the ocean quite believably. However, the developers' less-than-complete effort to model and animate these ships becomes apparent when they simply clip through each other. Other than structures that these ships have to dock with such as derricks and ports, their animations do not regard the hitboxes of any other objects.

The most apparent aspect of Tropico 3's audio designs is its musical soundtracks, which play throughout every part of the game unless turned off. The soundtracks consist of upbeat music, most of them being mariachi songs (appropriately enough, if a bit stereotypical). These songs may eventually get into the head of a player and would take a long time to be forgotten, so this is a warning to those who do not appreciate songs with lingering tunes.

Tropico 3 also has some very funny voice acting, most of which will be provided by Juanito, who is the DJ of a self-proclaimed independent radio station "TNT". Juanito's broadcasts range from statements that are dubiously sarcastic and earnest at the same time to the outrageously gleeful. Of course, Juanito would not endear to every player, but to those whom he does, he will be plenty entertaining to listen to.

The tutorial also benefits from good voice-acting too, despite how short it is. The instructions in the tutorial are given by a hilariously brown-nosing advisor called Penultimo, who will also add amusing commentary that kiss up to the player but also contains double-speak that hints of treachery.

The voice-acting for the President is not as amusing though. Kalypso has attempted to make him/her sound megalomaniacal, but the end result may simply sound snobbish to most players.

The voice-acting of the Tropicans and tourists is not as annoying, but they are not as amusing as either Juanito or Penultimo. The Tropicans speak in what sounds like a dialect of Spanish, whereas tourists speak in a multitude of languages, but there is nothing remarkable to be heard from them.

The default camera height is such that the player will not be hearing many sound effects beyond the honks of cars and groans of heavy machinery, among other loud noises. Being zoomed out all the way to the maximum height pretty much blocks out anything, but in return for the convenience of being able to scroll across the island quickly. Zooming in up close allows the player to appreciate the many sound effects that occur at street level, such as the chatter between Tropicans interacting with each other, but generally this is only for whiling away time.

In conclusion, Tropico 3 has some game features that still seem lacking, such as control over the army's deployment, but the rest of the game is quite well done. Tropico 3 is a great entry to the Tropico series, and an especially pretty one too.