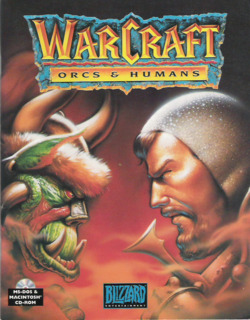

After having made games like Lost Vikings and Rock N' Roll Racing that had the effect of tiny pebbles dropping into a pond, Blizzard produced this game, whose huge, splashing entry into the shallow pool that was the RTS genre eventually summoned the waves that would soon turn said genre into an ocean of many currents.

Following the ground-breaking design model of Dune II, Blizzard had created the next functional and truly fun RTS game (though neither by any means were the first few RTS games ever to be made - there were even older ones). Blizzard certainly had built upon advancements that Westwood had made in the RTS genre.

The game has a pleasing user interface (UI) that hides much of its command-prompt-driven build. Thematic finishes to said UI further improves immersion. The game also appears to have a good incorporation of keyboard support, with clear tool-tips and textual instructions on what to do after activating each unit command, for example.

Graphics of games at the time tend to look like slap-dash work, especially if they involved imposing models onto otherwise blank templates. Warcraft was no different. Buildings and units, with their complete lack of shadows of any sort, certainly looks like they have been super-imposed onto the map, with the bigger ones looking especially awkward. Still, they have a tremendous amount of detail (for games of that time), especially the Humans' buildings.

Terrain features appear to better meld into the backdrop. They also have enough details to hide well the fact that they are largely repeated throughout every portion of the map where they appear.

Warcraft's tale and themes were not exactly original, even back then; the plot of an otherwise peaceful land being invaded by otherworldly savages was an old one, as was the rising of a resisting force against this onslaught. The characters were also heavily inspired by the works of Tolkien and (perhaps even more so) Games Workshop's Warhammer Fantasy Battles. Of course, it was not a run-of-the-mill "good-versus-evil" set-up, but the gray areas of morality and the shaky justifications used by the main characters for having done what they did were not exactly ground-breaking.

Nevertheless, the plot development did a very good job of unfolding the game's campaign, which gradually introduced the player to the mechanics of the game and the types of units available to either of the game's two feuding factions. (It also happened to set the groundwork for the sequel, which would then make an even greater impact on the RTS genre.)

The gameplay was certainly different than that of Blizzard's previous games, namely Lost Vikings and its first (and possibly last) racing game. Like Dune II, the player is required to establish a base (called a 'town' here, but it functions pretty much in the same manner), collect resources from nearby nodes of resources (gold mines in this case) or patches of them (e.g. copses of practically impenetrable forest). However, unlike Dune II, resources are very much exhaustible in this game: forests can be plundered bare and gold mines completely mined hollow. This is not a new game design, which is intended to force the player to consider carefully the rate at which they raise units and expend them in battle.

That said, training units and erecting buildings require either one or both types of resources to be performed, further requiring more planning on the part of the player. This is not a game where a player can power-build himself/herself to the top tiers of units or spam huge armies quickly. Also, there are unit upgrades that compete with unit training for the funneling of resources.

Speaking of units, the game has rather identical counterparts for either faction: Footmen practically mirror Grunts, Knights & Raiders are practically the same units, etc. The only real differences between the two factions are their spell-caster units, who appear to have spells of different effects. However, the same differences, intended to shake up gameplay when high-level units are available, also fueled an imbalance of sorts.

On that note, using the Humans' Clerics does require more than a bit micromanagement, which certainly puts the player at a disadvantage against the more omniscient and quicker AI, but whose Invisibility abilities would come in handy in battles against human players instead. The Orcs' summoned Daemon is a near unstoppable powerhouse that require either frantic kiting to slay, or a gaggle of melee units to be sacrificed in battle with it just to send it back where it came from. The Humans' Water Elementals are weaker, but having powerful ranged attacks probably made them even worse than Daemons.

Sound-wise, it could be alleged that the first Warcraft game started the trend of fully providing voice-over to every unit. While many units do appear to share voice-overs, there are enough variations to avoid them from sounding too repetitive (at least for the standards of its time). That said, even the buildings have their own voice-overs, a pleasant quirk that was not very common during the game's time. Other than that, the other sound effects in the game were very much what one would expect from an MS-DOS game: tinny sounds of metal striking each other, and blooping noises for wounds being inflicted, for instance.

Perhaps one of the greater contributions of Warcraft: Orcs and Humans to the RTS genre was its random map generator. Having been around before in less conflict-oriented strategy games (namely the Civilizations series), Blizzard's game effectively incorporated a random map generator for the benefit of single-player skirmishes and multiplayer. With it, the need to memorize maps to gain an advantage over other players was eliminated, thus making matches somewhat fairer and fresher.

All in all, one could say that Warcraft: Humans and Orcs laid the foundations for what would become the defining features of competent RTS games, and for this, the game deserves significant lauding.