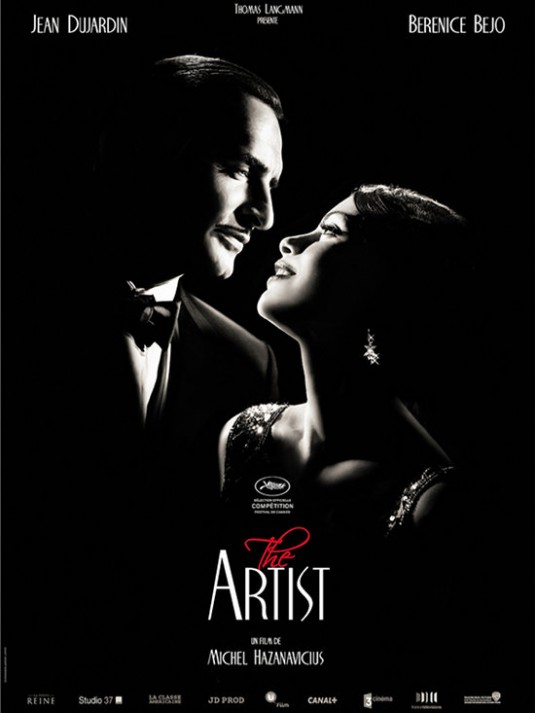

In 1927 silent film star George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is at the top of his game. People can't seem to get enough of him and his sidekick, a Jack Russell named Uggie. After a screening of his latest film he literally bumps into a young woman named Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), who briefly steals his limelight because everyone is wondering who she is. Valentin's boss Al (John Goodman) is unhappy when she draws attention away from the film's opening. Peppy is aspiring to be an actress herself and ends up on the same studio lot as Valentin, auditioning for a part in his movie. A more drastic encounter arises for Valentin when Al shows him a glimpse of the future of cinema: the arrival of sound in movies. Valentin's refusal and inability to adapt leads to the decline of his career and marriage, his friendship with his driver Clifton (James Cromwell), along with his mental wellbeing too.

Our value of cinema lives inside the phrase 'seeing is believing'. Film is a visual medium and we regularly find that movies dazzle us through the uniqueness of their stylistic form, rather than the distinctiveness of their thematic concerns. James Cameron's Avatar (2009) for example, is the instigator of the 3D rebirth, the highest grossing film of all time, but also a B-grade action film dressed in sheep's clothing. The Artist is at the other end of the spectrum. On a budget of just fifteen million dollars, French director Michel Hazanavicius has the impossible task of making the silent film era attractive for audiences again. Just like Avatar, it is the visual form and styIe of this film, rather than distinct themes, that are its defining qualities. This is not to say that the film is lacking in depth. A small minority have criticised the film for being 'styIe over substance'. Since when is image, if it is used to create meaning, not be regarded as deep or substantial? As a silent film today, The Artist is an affectionate tribute and homage to a period where films told stories and developed themes almost entirely through images. The only dialogue here is selectively provided through onscreen title cards. Due to the expressiveness of the actors and the film's outstanding formal composition though, these are rarely needed. Hazanavicius is said to have studied the techniques of the silent era extensively and it shows in the quality of the impeccable filmmaking. With its precise, direct camerawork, shooting in the traditional silent era ratio of 1.33:1, The Artist could make a seamless transition back into the very era it is recreating. Great efforts have placed into heightening the mood of the piece, through dim lighting and shadows that detail an era of economic uncertainty. The film was first converted to black and white but Hazanavicius also employs what is called sepia toning, essentially a brown filter, to reflect the changing quality of the film stock over the years.

Although the film is silent for much of its length, there are select moments where sound is cleverly employed for dramatic impact. Deep into the film, Valentin has a dream where the sound of every person and object in his world is amplified. Raising the diegetic sound to these booming levels reminds us of its shattering power and intrusiveness over silence, while also enhancing the psychology of Valentin, who fears that this is the future of his entire life. While in isolation these techniques could be cynically viewed as gimmicks, along with the visuals they are employed to tell a story about the attractiveness of fame and in equal measure, its fleetingness too. Consider the subtly and the economics of storytelling in the following images: when we first see Valentin's home it is handsomely decorated with ornaments and artworks, including paintings of himself. Yet during his downfall even the essential furnishings of his house are barely visible. Entering Peppy's accommodation during her own and its eerily similar to Valentin's, reflecting the reversal of their fortunes. Two of the more distinctive or flashier shots in the film speak volumes about Hollywood. The first is a long shot, held for what seems an age, on a staircase in the film studio. The framing of both the rising and falling stairs shows that regardless of the state of your own career, show business rolls on without you. This is also reflected in a low angle shot of Peppy's billboard, towering over Valentin, alone in the street, realising that a new generation of younger and more adaptive performers have arrived. Further contributing to the story are the performances of Dujardin and Bejo, both of which are faultless in their expression of two people at different stages in their careers. The subtly and the selection of their body language tells us so much about their characters. Two really entertaining performances, three if you include the funny little dog Uggie, are on display here.

Despite the formal strengths and the quality of the performances, I wondered how well a story with more complex or distinct themes, rather than large, broader ones that bode well visually, would have fared under the restrictive conditions of silent cinema. They wouldn't have. Great dialogue is not a gimmick as people once thought. It is a powerful tool, used to strengthen more challenging themes and characters. There are certainly some sharp title cards here but I love films of constant wit and detail, where the most intricate or humorous line of dialogue is spoken in such a way that it adds layers to a character's complexion, history and desires. The Artist finds clever ways of visualising grand but very familiar themes, like fame, technology and generational change to tell a likeable and accessible story. Amidst the boring CGI avalanche, where both theme and storytelling are disregarded, we hail a film like The Artist as fresh because of its unique formal styIe and identity. Save for one very tense moment towards the end of the film though, the story is funny and charming but entirely predictable. The direction of the narrative rarely surprises or moves us, mostly because it owes much to the superior Singin' in the Rain (1952), which covered the transition into the talkies with greater specificity towards the filmmaking process. It is also a serious disadvantage to have seen The Artist's overly revealing trailer beforehand too. With help from one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood, Harvey Weinstein, whose company distributed the film, The Artist may very well win the Best Picture Oscar. For me, Hugo (2011) will always be the superior film. It intertwines a clever mystery surrounding silent cinema, with 3D technology, to develop interesting, unique themes about the mechanical nature of humanity. It is a great film that satisfies our cinematic desires for the old and the new. While I appreciate The Artist's bravery and craftsmanship, I am not ready to call it a masterpiece.

Log in to comment