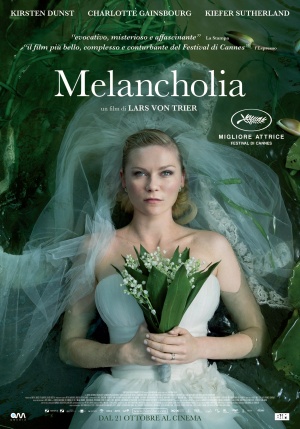

Melancholia is divided into two chapters. The first is entitled "Justine" and focuses on a bride named Justine (Kirsten Dunst) and her partner Michael (Alexander Skarsgard), who are attending a party at a manor house. To the annoyance of her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and her husband John (Kiefer Sutherland), both of whom have spent time and money organising the party for them, the couple arrive extremely late. The party is occupied by various friends and family. Most bizarre are Justine's parents who have separated and Justine's boss who has her followed. Their behaviour prompts Justine to find excuses to leave the guests and head outside. In the night sky is the planet Melancholia, which we are told is closing in on the Earth, with a chance of both worlds colliding. As the night continues, Justine's behaviour grows increasingly irrational. The second part of the film is named "Claire". It concentrates on how she is trying to help Justine recover, as well as her fear of the oncoming planet too.

The bad boy of cinema hasn't changed. The controversial Danish director Lars von Trier, founder of the abstract film movement Dogme 95, has forgone the nastiness of his previous films and retreated to a more conventional aesthetic styIe. There are thankfully no invisible doorknobs in Melancholia. It's visually spectacular at times, with appreciation towards the scope and grandeur of outdoor landscapes. While the styIe might have changed, the same mind games are intact, making this still very much a von Trier film. We're distracted by the film's lunacy, black sense of humour and sci-fi tropes but at its core it is a film about how two different women respond to death. That is very personal issue for von Trier, an admitted depressive, who claims to use filmmaking as a form of therapy. Melancholia seems like a more accessible story for the director to express himself through but there are familiar tricks at work. A common technique in von Trier's films, one that's sustained here, is his reliance on avatars rather than traditional character arcs. Characters in his films appear normal on the surface but then subvert their image through aberrant behaviour.

Using the image of a bride is smart because it feels less contrived than David Morse's bad cop in Dancer in the Dark (2000). The anxiety that a woman must feel towards marriage is understandable. Physically embodying this tentative role is Kirsten Dunst. She finds the perfect balance between concealing her unrest from the other guests, while selectively revealing her personal conflict to the audience through von Trier's tight close-up shots. The first half of this film genuinely shows her range and her cIass as an actress. She is aided immeasurably by von Trier's intelligent visual design too. The shifts in her personality are reflected in the film's lighting. The wedding party scenes, complete with fake smiles, are brightly lit and juxtaposed against the backrooms and manor grounds, which are dim and shadowy. Rather seamlessly, it shows the transition between each avatar's surface appearance and their true personality. There's a chilling scene where John intimidates Justine in the backrooms, revealing his own personal conflictions.

For much of the film's aesthetic control, there are a lot of strange details that are never explained. Still wearing her wedding dress, Justine climbs into a golf buggy, drives off into the night and then relieves herself on the course. One of the pleasures of Justine's dad (played by John Hurt) is to antagonise the waiters by putting spoons in his pockets and then calling the waiters to replace them with new ones. My favourite is the organiser who declares Justine has ruined the wedding and every time he walks past her he covers the side of his face. The first chapter is brimming with strange, sometimes funny, threads like this. I laughed at many of these oddball characters, assuming it was meant to be funny and intentionally absurdist. The oddity of the piece makes it appealing but it is also dramatically rich enough that it could have expanded into an entire film.

It is all the more disappointing that the second chapter, focussing on Claire, is dreary and morbid. All of the darkly funny characters are missing and Dunst's fine work isn't sustained because the emphasis rests on Gainsbourg's character. She can carry big scenes of emotion like she did in Antichrist (2009) but her character's hysteria over such an unlikely event is difficult to sympathise with. Worst still, we realise the purpose of the flawed side characters from the first half. The separation of a woman from the foundations of life, from her marriage, her job and her unlikeable family is, I think, reflective of von Trier's aversion to the American Dream. Justine, becoming a stark alien-like figure, announces that the Earth is evil and willingly accepts death because she will be free from the self-importance of others. Von Trier contrasts this attitude with Claire's protection of her child but given the film's inevitable resolution there is little question of which woman he sides with more. It is not a view of the world that I could ever find agreeable but that's Lars von Trier isn't it?

Log in to comment