In the mid 1980's, an ordinary West German by the name of Markus Hess did something completely extraordinary. He was able to break into the most secure building in the United States, the Department of Defense Headquarters at the Pentagon, and he did it all without ever leaving his flat in Hanover. This is the story of (almost) precisely how he did it, with some other interesting cases thrown in for good measure. I hope you find it both intellectually stimulating and interesting. Also, I do not pretend to be an expert here, so any inaccuracies or missing information are accidents on my behalf, for which I apologise.

The stereotypical image of a "hacker" is of some lonely and isolated guy, highly intelligent and normally geekish in nature, sitting in a small darkened room, quickly and conspiratorially tapping away as he breaks into the National Bank of Zurich and extracts a comfortable sum in easily exchangeable amounts. In fact, the truth is that most of the famous hackers were completely ordinary members of society, who lead completely average lives before taking up their illegal exploits.

The first hacker is often said to be John Draper (often nicknamed 'Captain Crunch', see picture), who in the late 1960's discovered with his friend Joe Engressia (renamed "Joybubbles") that a toy whistle included in a packet of "Cap'n Crunch" breakfast cereal could be easily modified to have a tone of precisely 2600 hertz. Whilst this would seem inconsequential to the casual observer, Draper knew that this tone was the same as the AT&T long distance reset signal, which indicated that a truck line was ready for a new call. Routing the tone down the line during dial would disconnect the other end of the call, allowing the still connected end to effectively become the operator, thus letting allowing the placement of calls for free. Though the process was part of the "phreaking" phenomenon (manipulation of telecommunication devices), it is still one of the first recorded cases of hacking.

The most famous phreakers however, are still Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, the founders of the Apple Computer Inc. Before starting their computer company, they enjoyed free prank calling a using so-called "blue box" machine which could simulate the 2600 hertz tone. One famous incident in 1971 included Wozniak dialing Vactican City, claiming to the US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (even putting on a German accent), calling on the behalf of President Nixon, and asking to speak to the Pope at once. However, he was asked to call back, as the Pope was sleeping. When he did call back, an angry Bishop told him that he had spoken to the genuine Kissinger in Moscow during the intervening time, upon hearing which Wozniak hung up.

It is "The 414s" who really established what it was to be a hacker. They were a group of six ordinary teenage boys from Milwaukee, who had taken their name from the area code of the district where they lived. They met as part of their Exploring Boy Scouts group, became friends, and then competed with each other to break into high-profile computer networks. Between 1982-3 (coincidentally the same time the hacking-influenced film 'WarGames' was released), they broke into over sixty systems, including the Security Pacific Bank, the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. The FBI quickly caught up with the group, and although the only charges brought against them were "making harassing phone calls", the event raised many alarm bells amongst security experts. The group perfectly matched the profile of hackers, the FBI describing them as; "young, male, intelligent, highly motivated and energetic." When 17-year-old Neal Patrick was asked why he did it, the answer was simple; "just to see if I could do it." Although they did little real damage, the Sloan-Kettering Center had to spend $1,500 reconstituting deleted files, which the 414s had got rid of to cover their tracks. In fact, there was substantial public interest into the group, to the extent that several were featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine.

The 414s were useful in showing computer experts that others with more malicious intent could theoretically duplicate their techniques and do genuine damage to computer infrastructures. However, it was still seen mainly as a prank, and not something dangerous. It was also at this time that the House of Representatives first began hearings on security hacking, although they were treated with minimal interest. In 1984, one of the first cases of hacking in the United Kingdom emerged. Robert Schifreen was tried after being found hacking into the British Telecom (BT) central computer, making him able to read the personal mail of His Royal Highness Prince Philip. Naturally, the prince was rather miffed at this news.

And so enter Markus Hess, and a real Cold War conspiracy. Hess, a renowned hacker, had been hired secretly by the KGB to be an international spy, and pass secrets to the Soviet Union by hacking into the US Military Network (MILNET) part of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET, what would one day become what we know today as the Internet). Throughout the course of his hacking, he only ever used his home computer and an ordinary modem. First, Hess began by gaining some passwords to the network at his local Hanover University. Posing as a student, he was able to log on to the European Academic Research Network, which connected computers across European universities. From here, he broke into a computer at the University of Bremen, where he was able to access the national German DATEX-P Network. Using a satellite relay, Hess used the DATEX-P to bounce his signal around the world, and connected to the Tymnet International Gateway in San Jose, California.

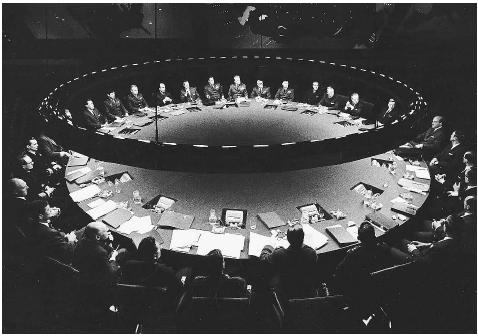

The Tymnet, a system purposefully designed to route the user to any other computer system on the service, put Hess in communication with the Jet Propulsion Laboratories in Pasadena (a testing facility for NASA), and through it the Tymnet Switching Service, which allowed Hess to redirect his signal to yet another computer. This time it was to the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in Berkeley. As it is today, the Laboratory was involved in a number ofrestricted research projects for the Department of Defense, and as such connected to ARPANET, so the Department could be updated on developments. It was therefore easy for Hess to "piggyback" his way into ARPANET through Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. Pretending to be a "Colonel Albrens" with a codename of "Hunter", Hess accessed the secure MILNET, and finally made his way to the OPTIMIS Database at the Pentagon. Over two years, from 1986-8, Hess accessed, read and copied many Top Secret files concerning everything from spy satellites to nuclear warfare, attacked over four hundred military computers, and hacked into dozens of secure facilities, including amongst others SRI International (the research institute), the US Coastal Systems Computer, Air Force Systems Command and Army Darcom.

During these two years, the Department of Defense had absolutely no idea that anyone had got into their systems without permission. The person who actually discovered Hess' activities was not even a formally trained computer expert, and in the end found Hess because of a simple accounting error. Clifford Stoll (see picture) was an astronomer, who had recently become the systems administrator at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. At the laboratory, users had to pay for the time they spent accessing ARPANET, and also had to get privileges to do so. Naturally, Hess had no such privileges, and did not pay for the time he spent online, but had hacked to become a "root" or superuser, allowing unlimited use. So, when Stoll was calculating the laboratory usage accounts he discovered that there was a seventy-five cent (or thirty-eight pence) shortfall. Most people would have ignored such an insignificant amount, but Stoll was determined to find out why his sums did not add up correctly.

He quickly ascertained that the reason there was an accounting shortfall was because more time had been used on the network than had actually been paid for, and since all members of the laboratory staff were correctly accounted, the only option left was that someone else had hacked in and was using time illegally. With the help of the local telephone company, Stoll found out that the unauthorized incoming signal had originated from the Tymnet Switching Service at Oakland, California, proving that the hacker was not working locally. After contacting Tymnet officials, he was able to trace the signal back further to the MITRE Corporation Headquarters (a defence contractor) in McLean, Virginia. Using a teletype printer connected to the intrusion at MITRE, Stoll could watch as Hess accessed therestricted documents, and took notes on his activities. This has been identified as the first documented case of "cracking" a system.

Stoll saw that the hacker normally accessed the ARPANET in the middle of the day Pacific Time, and since most programmers tended to work at night, surmised that the hacker was in a time zone in Europe. Stoll also was amazed at how many high-security sites the hacker could easily guess the passwords. It seemed that many administrators had never bothered to change passwords from factory defaults. Even at many Army bases the hacker was occasionally able to login as "guest" using no password at all. During his investigation, Stoll contacted the FBI, CIA and NSA, although all three were reluctant to share information with each other, or even gain jurisdiction to investigate the issue. Stoll remembers a NSA agent as saying "we listen, we don't talk".

Eventually, Stoll was able to work out that the signal was coming from West Germany through the DATEX-P satellite. The Deutsche Bundespost (the German Post Office) who at that time had authority over the telephone system, had traced the signal to Bremen, but knew it was rerouting from somewhere else. So that the Bundespost could back-trace the signal for long enough to ascertain the source, Stoll devised a cunning plan. He knew that the hacker was very interested in the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), so created an account (the SDINET) which appeared to contain very important information about the initiative. As luck would have it, Hess accessed the account almost at once, and so the Bundespost traced him finally back to his flat in Hanover, where he was arrested. There was also supplementary evidence when a Hungarian spy contacted the fake SDINET, something he couldn't have done without information from Hess. It later turned out that this was the way the KGB double checked that Hess was giving them genuine information rather than just making it up.

Hess was put on trial in 1990 in Germany and Stoll testified against him. Hess was found guilty of espionage and was sentenced to three years in prison. Clifford Stoll's work into catching Hess was frankly incredible. He had made full records of Hess' activities, whilst his logbook evidence was unquestionably detailed. After Hess broke into the MILNET, the Department of Defense became a lot more stringent about tightening security around their computer systems. Computer crime was now something that was taken very seriously.

P.S. Aha, thank you for clarifying that fact GameSpot, I noticed that update you made. I was simply experimenting with the boundries of the Soapbox, to see what could get spotlighted. In future, I will be sure to only stick to "gaming related" entries. ;)

Log in to comment